There’s a specific kind of betrayal that happens when you revisit an anime you loved as a teenager, expecting the same rush of excitement, and instead get psychic damage from recognizing your department manager in a character you once thought was cartoonishly evil.

The show didn’t change. You did. And not in the inspiring, coming-of-age way anime promised you would.

You got a job. You saw how meetings actually work. You watched someone’s career implode over office politics that had nothing to do with competence. You realized that “just work harder” is advice given by people who’ve never had to choose between fixing their car and making rent, and that sometimes the villain’s plan makes perfect economic sense if you’re the one holding the spreadsheet.

This isn’t about nostalgia goggles breaking. It’s about finally having the reference points to understand what was always on screen. Anime didn’t lie to you when you were fifteen, you just weren’t equipped to recognize the truth it was depicting.

The Workplace Was Always The Horror

Neon Genesis Evangelion gets credit for psychological depth, existential dread, religious imagery that doesn’t quite mean what Western viewers think it means. What rarely gets mentioned is how accurately it depicts a catastrophically mismanaged organization held together by institutional inertia and one person’s unprocessed trauma.

NERV functions like every dysfunctional workplace you’ve ever seen, scaled up to apocalyptic stakes and dressed in paramilitary bureaucracy.

Gendo Ikari doesn’t read as a mysterious mastermind when you’ve watched a director tank a project because they refused to communicate the actual goal to their team. He reads as every manager who mistakes withholding information for leadership, who thinks emotional unavailability projects authority, who’s so committed to a personal vision that they’ll burn through employee welfare to achieve it. The committee scenes—those interminable moments of old men talking in dark rooms—aren’t narrative filler. They’re the exact phenomenon of watching executives have cyclical conversations that could have been emails, making no decisions, while the people doing actual work get zero support.

Misato runs her household like someone spiraling through burnout while pretending everything’s fine. Beer for breakfast isn’t quirky anime-girl behavior. It’s self-medication. Her apartment is what happens when you’re too exhausted from performing competence at work to maintain basic life infrastructure at home.

The show aired in 1995, during Japan’s Lost Decade—that stretch after the economic bubble burst when lifetime employment dissolved and the social contract that promised security in exchange for loyalty revealed itself as always having been conditional. Anno Hideaki was directing this while experiencing severe depression, and late-production constraints and scheduling pressures contributed to the show’s unconventional final episodes. The chaos on screen mirrored the chaos behind it.

NERV’s child soldiers aren’t a dystopian exaggeration when you understand the context of a generation being asked to solve problems they didn’t create with resources they weren’t given.

Economic Desperation Looks Different When You’ve Felt It

Cowboy Bebop follows broke adults doing gig work in space, and when you’re sixteen that sounds like freedom. No boss, no rules, adventure on your own terms.

Then you drive for a ride-share app, or freelance, or work contract positions without benefits, and suddenly Spike’s whole deal isn’t romantic anymore.

The Bebop crew aren’t cool loners. They’re people trapped in a permanent economic precarity that prevents them from building toward anything. Every bounty is the next rent payment. Every big score gets eaten by ship repairs, medical costs, or just putting food on the table. They’re not choosing adventure—they’re stuck in a cycle where survival consumes everything that might have been savings or investment in a future.

Episode 5, “Ballad of Fallen Angels,” shows Spike confronting his past, but it’s also about how you can’t actually move forward when you’re financially stuck. The past finds you because you never got far enough away. Episode 10, “Ganymede Elegy,” brings back Jet’s ex-lover, but the emotional beat only works because Jet stayed in the same economic bracket he was always in. People with resources get to reinvent themselves. Everyone else just ages in place.

The show aired in 1998, in an economy where the salaryman model was visibly failing but nothing had replaced it yet. Cowboy Bebop’s future isn’t about space travel—it’s about what work looks like when institutional stability evaporates. The bebop crew does the labor version of gig work before that was a widespread term, and the show never pretends it’s sustainable.

Faye’s debt—she wakes from cryosleep to discover she owes millions tied to medical care and legal exploitation—reads like absurdist sci-fi until you’ve seen medical bills in any privatized healthcare system. Then it’s just realism with a spaceship.

The Adults Were Always Broken (That Was The Point)

FLCL is six episodes of visual chaos, puberty metaphors, and robots emerging from a kid’s head. It’s also the most accurate depiction of how adults look from below: incomprehensible, vaguely threatening, completely absorbed in their own unresolved issues while a child tries to decode what maturity is supposed to mean.

Naota spends the series surrounded by adults who have no idea what they’re doing. His father obsesses over a washed-up baseball player. Haruko is literally using a twelve-year-old to work through her obsession with someone else. Mamimi clings to Naota because he’s safe—he can’t actually hurt her the way her peers can. Every adult in his life is either absent, dysfunctional, or actively making his situation worse while pretending to help.

At sixteen, this reads as Naota being surrounded by weird people. At thirty, it reads as every adult Naota knows being exactly as confused as he is, just with more expensive consequences for their mistakes.

FLCL is often described as a post-Evangelion release valve—playful, chaotic, and deliberately unstructured after the intensity of that production. The chaos isn’t style—it’s substance. It’s what the world looks like when you’re too tired to impose narrative order on it.

Mamimi’s photography—her constant documenting of things about to be demolished or changed—is what people do when they have no control over their environment. She can’t stop the development, can’t preserve the places that matter, so she records them. Every twenty-something with a phone full of photos they never look at understands this impulse perfectly.

When The Critique Was Always There (You Just Weren’t Looking At The Right Layer)

Paranoia Agent aired in 2004, and at surface level it’s a mystery: who is Lil’ Slugger, the kid on golden rollerblades attacking people with a bent baseball bat?

The answer is everyone and no one, because Lil’ Slugger is what happens when a society under pressure needs a release valve and collectively manifests one.

Kon Satoshi constructed the show as social commentary on Japan’s economic stagnation and the psychological toll of maintaining appearance while everything crumbles internally. Each character is trapped by different pressures—professional reputation, debt, social expectations, celebrity, family duty—and Lil’ Slugger appears when the gap between their public performance and private reality becomes unbearable.

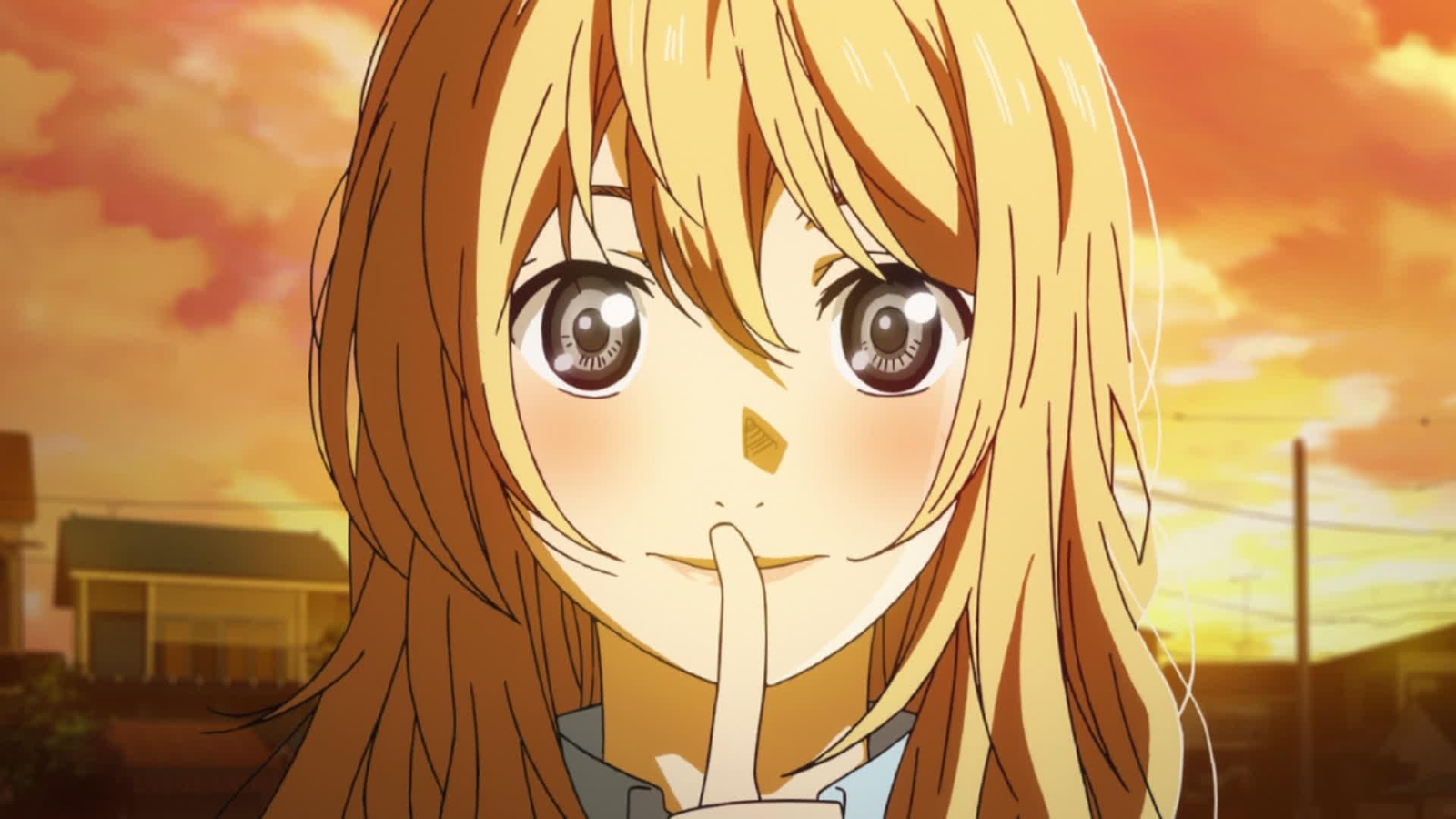

The first victim is Tsukiko Sagi, a designer whose creation—Maromi, a pink dog mascot—became a cultural phenomenon. She’s under crushing pressure to create a successful follow-up. When she can’t, Lil’ Slugger attacks her, and suddenly she has a legitimate excuse for failure. The attack isn’t random violence—it’s externalization of a pressure she can’t otherwise escape.

This logic applies to every victim. They’re not targeted randomly. They’re relieved.

At fifteen, this is a weird mystery show with unsettling vibes. At thirty, after you’ve watched colleagues have breakdowns, or had one yourself, it’s documentary footage. The show understands that sometimes people need to be hit by something external because admitting “I can’t handle this” isn’t culturally permissible. Lil’ Slugger is the socially acceptable breakdown.

Episode 8, “Happy Family Planning,” follows three people who meet online to commit group suicide. Lil’ Slugger barely features here—the episode doesn’t need him to be horrifying. The characters have found their own exit, and the episode plays it with such gentle, mundane realism that it’s more disturbing than any attack scene. They discuss methods the way people discuss weekend plans. The horror isn’t supernatural—it’s how normal despair sounds when people have processed it long enough to be calm about it.

The anime industry’s labor conditions are well-documented—young animators making below minimum wage, working 18-hour days, sleeping in studios. Paranoia Agent’s critique of societal pressure carries weight from an industry that understands those dynamics intimately.

The System Was The Antagonist (You Just Thought It Was A Specific Person)

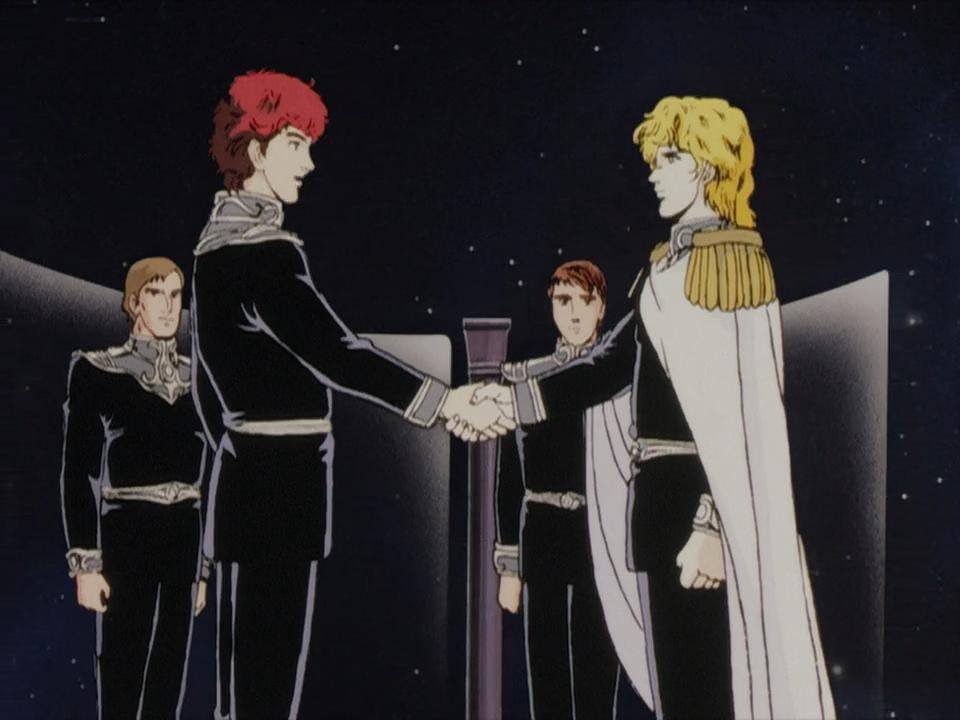

Legend of the Galactic Heroes is a space opera about war, politics, and two brilliant men on opposite sides of an ideological conflict. It’s also a detailed examination of how institutional systems persist regardless of individual virtue, and how even exceptional people are constrained by structures they can’t unilaterally change.

Reinhard von Lohengramm wants to dismantle a corrupt aristocracy. Yang Wen-li wants to preserve democracy. Both are trapped by the systems they’re operating within. Reinhard can’t reform the Empire without using authoritarian tools. Yang can’t defend democracy without military action that undermines democratic principles.

The show, based on novels by Tanaka Yoshiki, aired its OVA adaptation from 1988 to 1997. It’s deliberately paced—110 episodes of people talking in rooms, debating political philosophy, making compromises that erode their principles incrementally. When you’re young, this is boring. The battles are where the action is.

When you’re older, the conversations are where everything happens, and the battles are just consequences of decisions made in offices.

In the arc surrounding Yang’s assassination, what’s striking isn’t the death of a major character—it’s how the democratic system Yang died defending immediately fails to honor what he fought for. His allies use his death politically. His enemies feel vindicated. The institutions continue regardless of individual sacrifice, because institutions aren’t maintained by ideals—they’re maintained by incentive structures, and those haven’t changed.

The show understands that “good person in power” doesn’t fix systemic problems. Reinhard becomes emperor and discovers that changing laws is easier than changing the culture that interprets those laws. Yang serves democracy and watches it repeatedly choose short-term safety over long-term freedom. Neither man can transcend the system they’re embedded in, no matter how capable or well-intentioned.

This isn’t pessimism. It’s realism about how organizations function, and you only recognize it as realistic after you’ve tried to change something at work and discovered that individual effort breaks against institutional inertia.

What Looked Like Incompetence Was Actually Structural

Welcome to the NHK follows Satou Tatsuhiro, a hikikomori convinced that a conspiracy (the NHK, or Nihon Hikikomori Kyokai in his paranoid framework) is engineering social withdrawal. It’s played for dark comedy, but the longer you exist in modern economic systems, the less funny the conspiracy theory becomes.

Satou isn’t wrong that systems create hikikomori—he’s just personified it incorrectly.

The show aired in 2006, based on Takimoto Tatsuhiko’s semi-autobiographical novel. Takimoto has spoken about his own experiences with withdrawal and instability influencing the work. The story works as psychological character study, but it also works as economic analysis: Satou can’t get a job because he has no experience, and he can’t get experience without a job. He’s caught in a loop where the longer he’s out of the workforce, the less employable he becomes, which extends his time out of the workforce.

This isn’t laziness. It’s structural exclusion with a smile.

The show depicts Satou’s various schemes to make money—creating a bishoujo game, joining a multi-level marketing scheme, trying online counseling services. Each fails, but not because Satou isn’t trying. They fail because he’s attempting individual solutions to systemic problems. You can’t entrepreneurial-spirit your way out of an economy that doesn’t have space for you.

Misaki, who befriends Satou through a program designed to rehabilitate hikikomori, is herself barely surviving. She’s doing this volunteer work as her own escape from worse circumstances. The show’s dark joke is that the person trying to fix Satou is more desperate than he is, and neither of them has access to actual support systems that would address their material needs.

The final arc involves Satou’s uncle embezzling money and the whole family’s financial situation imploding. Satou’s withdrawal wasn’t happening in a vacuum—it was happening in a family unit that was itself precarious. The show reveals that Satou’s ability to be a hikikomori was funded by family money that was never secure, and when that evaporates, his problems don’t suddenly resolve through willpower. They just become different problems.

The Re-Watch Reveals What Was Always Visible

None of these shows changed. The animation is the same. The dialogue is identical. The directorial choices haven’t been altered.

What changed is the viewer’s frame of reference.

At sixteen, work is theoretical. By twenty-six, it’s 40+ hours a week of empirical data. At sixteen, economic pressure is something parents deal with. By twenty-six, it’s the gap between paycheck and rent, or the math on how long you can afford to be unemployed, or the decision between career progression and mental health. At sixteen, institutional dysfunction is abstract. By twenty-six, you’ve been inside the machine long enough to see how the parts don’t actually fit together—they just grind against each other while everyone pretends this is normal.

The anime you’re re-watching didn’t age badly. It aged you into recognition.

The shows were always depicting real conditions—workplace dysfunction, economic precarity, institutional failure, the gap between ideology and implementation. Younger viewers just lacked the experiential context to decode them. The robots and space bounties and mysterious attackers were never the point. They were the framing device that made the actual subject matter tolerable to discuss.

When people say an anime “aged badly,” sometimes they mean the cultural references are dated, or the animation looks rough, or the gender dynamics reflect a different era. Fair enough.

But when an anime feels heavier, darker, more uncomfortably accurate than it did before—that’s not the anime changing. That’s pattern recognition finally activating. The show handed you a map of adult life when you were fifteen, and you filed it away as entertainment. Now you’re walking the territory it charted, and the map suddenly makes sense.

The genre was always realism. You just didn’t have the reference points to recognize the landscape.