The Death Note fandom has spent two decades arguing about whether Light Yagami was right, wrong, or somewhere in the morally gray middle. But here’s the thing everyone keeps missing: Light was already fundamentally broken before Ryuk dropped that notebook. The Death Note didn’t corrupt a good person—it just gave a narcissist the world’s most dangerous permission slip.

And somehow, we’re still calling him a genius.

Sure, Light scored perfectly on exams and orchestrated elaborate murder schemes while eating potato chips. But actual intelligence and pathological narcissism wearing intelligence as a costume are two very different things. One solves problems. The other just needs you to watch while it does.

The story of Light Yagami isn’t about a brilliant mind succumbing to power. It’s about a deeply insecure teenager who finally found a way to prove he was special—and immediately started killing anyone who suggested otherwise.

The God Complex That Started in a Classroom

Light’s psychology doesn’t begin when he picks up the Death Note. It crystallizes there, but the foundation was already set.

Consider his life before Ryuk: top student, nationally ranked, admired son of a police chief, destined for Tokyo University. A perfect résumé that tells you absolutely nothing about who someone actually is. Light didn’t just achieve these things—he needed them. Not for what they represented, but for what they confirmed: that he was better than everyone around him.

Japanese academic culture in the 1990s and early 2000s—the context in which Tsugumi Ohba and Takeshi Obata created Death Note—was suffocating. The pressure wasn’t just to succeed, but to embody success so completely that failure became unthinkable. Light is the product of that environment taken to its psychological extreme: someone who internalized perfection as identity.

When he calls the world “rotten” in the first chapter, he’s not making a philosophical observation.

He’s announcing that he’s already separated himself from it.

The Narcissist Who Found His Mirror

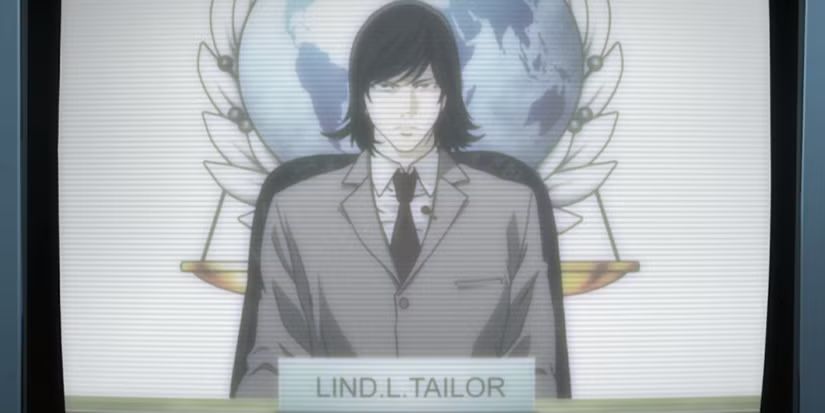

The Lind L. Tailor scene is where most people think Light makes his first mistake. The fake L broadcasts on television, taunts Kira, and Light—unable to resist—kills him immediately. Standard analysis calls this ego, impulsiveness, or pride.

It’s simpler than that. Light killed Lind L. Tailor because someone implied he wasn’t special.

Narcissistic supply—the validation that narcissists require to maintain their self-image—doesn’t come from quiet satisfaction. It comes from external confirmation, preferably public, preferably constant. The Death Note gave Light the ultimate form of supply: he was literally deciding who lived and died. God-tier validation.

But the second L suggested Kira might be caught, might be ordinary enough to make mistakes, Light couldn’t tolerate it. The notebook wasn’t even a week old and he’d already staked his entire identity on being its perfect wielder. Tailor’s death wasn’t strategic—it was reflexive. Like swatting at someone who interrupted you during a speech.

The Death Note didn’t give Light a god complex. It gave him an audience for the one he already had.

When Perfect Isn’t Good Enough

Watch how Light treats the people closest to him and you’ll see the pathology in action. His father, Soichiro, worships him. His mother and sister adore him. His classmates admire him. Takada and Misa both love him—or the version of him they’re allowed to see.

None of it matters.

Because narcissism doesn’t run on love—it runs on control. And love, real love, requires acknowledging someone else as equally complex, equally worthy. Light can’t do that. Every relationship he has is transactional. His father is useful until he becomes a liability. Misa is a tool who happens to be in love with her own utility. Takada is status and access. Even his sister Sayu only registers when she becomes a piece on the board during the Mello kidnapping arc.

The manga frames this through Light’s internal monologue, and it’s chilling how little he actually thinks about these people as people. They’re variables. Obstacles. Occasionally useful assets. When Soichiro dies, Light’s grief is real—but it’s the grief of losing something that reflected well on him, not the grief of losing a father.

There’s a reason Light never has a single friend in the entire series.

The Moral Decay That Never Actually Decayed

Here’s where the analysis usually goes: Light started with good intentions—reducing crime, creating a better world—but power corrupted him until he became the monster hunting him. The tragic fall from grace narrative.

Except Light doesn’t fall. There’s no grace to fall from.

His first kill is Kurou Otoharada, a criminal holding hostages. Self-defense by proxy, you could argue. His second kill, moments later, is a man harassing a woman on the street. Not a murderer. Not a hostage situation. Just someone Light decided deserved to die because… he could.

Two kills. Two minutes. Zero hesitation.

The speed is the tell. Moral decay takes time—rationalization, justification, gradual boundary erosion. Light skips all of it. He goes from “I’ll test if this works” to “I’ll cleanse the world” before he’s even processed what he’s done. That’s not corruption. That’s someone who was already waiting for permission.

Death Note was serialized in Shonen Jump starting in 2003, during a period when Japan was grappling with highly publicized youth crime cases and a perceived moral decline. The Sasebo slashing and the Nagoya abduction were fresh in public consciousness. Ohba and Obata created Light in that context—not as a hero or even an anti-hero, but as a character study in what happens when someone with zero empathy gets absolute power.

Light doesn’t lose his morals. He just stops pretending he had them.

The Performance of Intelligence

The potato chip scene—”I’ll take a potato chip… and EAT it!”—has become a meme, but it’s also a perfect encapsulation of Light’s pathology. He’s not just hiding his actions from the cameras. He’s performing brilliance. The elaborate setup, the dramatic internal monologue, the theatrical execution.

No one is watching except the audience.

That’s the point. Light doesn’t just want to win—he wants to be seen winning, even when there’s no one there to see it. His intelligence isn’t a tool for solving problems; it’s a stage for proving he’s smarter than everyone else. Every scheme is overcomplicated because the complication itself is the performance.

Actual strategic thinking involves efficiency. Light’s plans involve making sure everyone knows how clever he is, which is how he ends up in increasingly convoluted scenarios that a simpler approach would have avoided. The Yotsuba arc, the fake rule in the Death Note, the elaborate memory gambit—they work in the narrative, but they’re also wildly unnecessary risks.

Because the risk is part of the thrill. Not of potentially losing, but of proving he won’t.

The Inevitable Collapse

Light’s downfall is usually framed as L’s brilliance or Near’s logic or Ryuk’s betrayal. But Light defeats himself long before the warehouse scene. He defeats himself the moment he decides that being Kira is more important than surviving as Light Yagami.

Narcissists can’t quit. They can’t walk away from supply, even when walking away is the rational choice. After L’s death, Light has effectively won. He could stop. He could let the world believe Kira died with L. He could live his perfect life, marry Misa or Takada, become whatever he wanted.

But that would mean admitting the performance is over.

So he continues, because stopping would be the same as losing, and losing would mean confronting the possibility that he was never actually special—just a teenager with a magic notebook and an untreated personality disorder.

The final scene, where Light is dying in the warehouse, begging Ryuk to write names, reduced to screaming about his godhood while bleeding out—that’s not tragedy. That’s exposure. The mask finally breaks and there’s nothing underneath except the desperate need to be seen as something more than human.

Ryuk writes his name because, in the end, Light is exactly as boring as every other human who picked up the Death Note.

Just another corpse who thought he was different.

The God Who Never Was

Death Note ends with Light’s death, but his ideology persists. There are Kira supporters, people who genuinely believed in his vision of justice. The story doesn’t dismiss them—it shows that Light’s appeal was real, even if Light himself was hollow.

That’s the uncomfortable part. A narcissist with no genuine moral framework still created something people believed in. Not because Light was right, but because he was convincing. Because performance, when executed perfectly, is indistinguishable from substance until you look too close.

Light Yagami wasn’t a genius who became a monster. He was a narcissist who finally found a mirror that reflected godhood back at him. The Death Note didn’t corrupt him—it just made visible what was always there.

And somehow, we’re still arguing about whether he had a point.