Truck-kun has a perfect kill rate and zero remorse.

This unnamed delivery vehicle has ushered more Japanese salarymen into fantasy worlds than any magical portal or divine summons. It appears without warning, strikes without prejudice, and never once questions whether its victims actually wanted to cross that street. The phenomenon is so ubiquitous it’s become a joke—another forgettable protagonist, another unremarkable death, another world that conveniently needs saving by someone with precisely zero qualifications.

But here’s the thing nobody wants to say out loud: Truck-kun isn’t random traffic. It’s a mercy killing.

Every single one of those protagonists was already dead. They were just still walking around, and apparently, that needed correction.

The Protagonists Who Stopped Living Before They Stopped Breathing

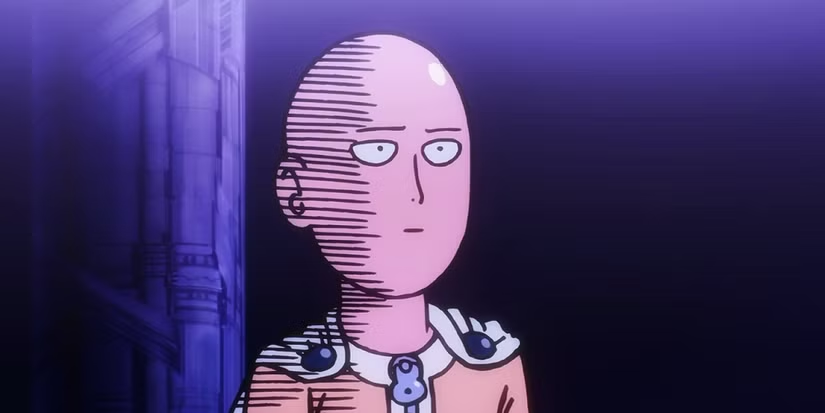

Satou Kazuma from KonoSuba died saving someone he thought was in danger. The punchline? There was no danger. He had a heart attack from sheer panic after seeing what he believed was an oncoming truck, then died from the shock while a tractor slowly rolled by. The universe looked at his pathetic NEET existence and said, “You know what? We can work with this level of delusion.”

That’s not a tragic accident. That’s assisted suicide with paperwork.

Look at the actual lives these protagonists are leaving behind. Subaru Natsuki from Re:Zero was a shut-in who’d abandoned his education, spending his time in convenience stores instead of building any kind of future. His death-by-summoning wasn’t interrupting a promising trajectory—it was cutting short something that had already stopped moving forward.

The pattern repeats with mechanical precision. Momonga from Overlord was a salaryman whose entire social life existed inside a video game that was about to shut down, severing his last connection to anything resembling human interaction. The 34-year-old NEET from Mushoku Tensei had become so isolated that his own family skipped his funeral.

These aren’t people with attachments. They’re people who’d already severed them.

Karoshi Doesn’t Always Happen at the Office

Japan has a word for death from overwork: karoshi. It entered the national lexicon in the 1980s during the bubble economy, when young salarymen were dropping dead at their desks from strokes and heart attacks. The concept gained increasing recognition through the late 1980s and 1990s as the government developed certification criteria and compensation systems. The phenomenon was severe enough that tracking systems were eventually established—though the actual numbers are almost certainly higher than official reports suggest because of underreporting and cultural shame.

Isekai anime emerged as a dominant genre in the 2010s, decades after karoshi became embedded in Japanese consciousness. Whether this timing represents direct causation or simply reflects broader anxieties about work culture is debatable, but the thematic resonance is impossible to ignore.

But here’s where it gets darker: karoshi is just the spectacular version. The boring version is what happens to everyone else—the people who don’t die at their desks but spend 60-80 hours per week in offices that demand total loyalty while offering none in return. The ones who miss their children growing up, who develop stress-related illnesses, who look up one day and realize they’re 40 years old and have never once done something they actually wanted to do.

That’s the world isekai protagonists are leaving. Not occasionally—consistently.

The truck isn’t interrupting their lives. It’s ending their sentences.

The Psychology of Controlled Demolition

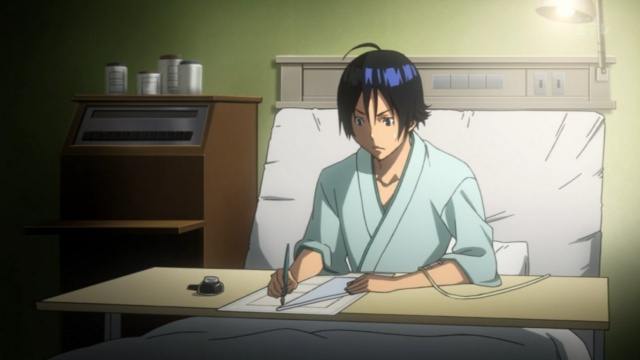

Mushoku Tensei opens with its protagonist—a 34-year-old NEET—getting hit by a truck while trying to save three high school students. The story frames this as redemptive: his first selfless act in years. But watch what the narrative actually does. It immediately reincarnates him as Rudeus, giving him a completely clean slate in a world where his previous failures don’t exist and can’t follow him.

That’s not redemption. That’s witness protection.

The function of the truck death is to create a hard reset that the narrative can present as fate rather than choice. Japanese employment culture traditionally emphasizes lifetime commitment—the education system tracks students early, and changing careers carries significant social stigma. The expected path is to pick your lane in your early twenties and stay there.

Unless you die.

Death becomes the ultimate narrative permission slip. It’s the one form of departure that can’t be characterized as giving up or running away because the decision was made by a F-150, not the protagonist. The truck removes agency and therefore removes judgment. You didn’t abandon your responsibilities—physics made an executive decision.

This matters because the psychological profile repeats across protagonists: they’re people who’ve already mentally checked out but lack a socially legible exit. Subaru had stopped investing in his future. Kazuma was paralyzed by the gap between his NEET reality and any functional path forward. Momonga was watching his last meaningful connection literally shut down.

The truck just formalized what they’d already decided.

When Death Is More Appealing Than Tuesday

The Devil Is a Part-Timer flips the script by sending the Demon Lord to modern-day Japan, where he ends up working at MgRonald’s (a parody of McDonald’s). It’s comedy, but the horror is right there in the premise: even a literal demon from another world can’t escape minimum wage service work and corporate hierarchies. The show accidentally asks the question that isekai protagonists are trying to avoid: what if there is no escape?

Because here’s the math that isekai understands perfectly: being murdered by the Demon King sounds more appealing than 40 more years of TPS reports.

That’s not hyperbole. That’s the actual value proposition. Die now and wake up in a world where your choices matter, where you have agency, where defeating the Demon King might actually solve problems instead of just creating quarterly earnings reports. Or don’t die, and spend the next four decades in a society that’s been in economic stagnation since 1991, where social mobility is limited, where the population is declining, and where the future looks like the present but slightly worse.

When you frame it that way, the truck starts looking less like transportation and more like salvation.

The Japanese fertility rate hit 1.26 in 2022—the lowest on record, and it’s continued falling since. Young people aren’t having children. They’re not getting married. They’re not investing in futures they don’t believe will improve. Whether or not this directly explains isekai’s popularity, the genre certainly offers the only form of future-oriented thinking that doesn’t require optimism about the actual future.

The Resurrection Fantasy Nobody Admits

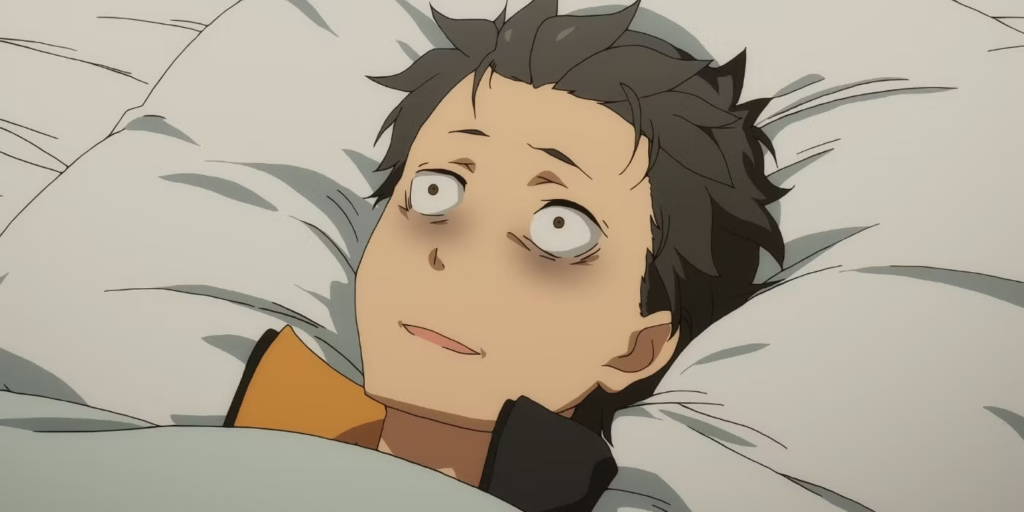

Re:Zero is secretly the most honest isekai because Subaru keeps dying and coming back, forcing him to experience the truck-kun moment over and over. Except it’s not a truck—it’s witches, cultists, rabbits, his own incompetence, and occasionally the person he’s trying to save. The method changes but the function stays the same: death as a reset button.

The show’s entire emotional architecture is built on Subaru’s inability to permanently die, which sounds like torture until you realize what it’s actually depicting. He gets to keep trying. He gets infinite attempts to get it right. He can fail catastrophically and still come back.

That’s not a curse in a culture that heavily penalizes failure. That’s a miracle.

Because the real world doesn’t work that way. You fail the entrance exam to the right university? Your career ceiling just got lower. You miss the recruitment window for lifetime employment? Enjoy contract work. You make the wrong choice? That follows you. There are no do-overs, no second chances, no Emilia who’ll smile at you the same way even though you’ve died seventeen times.

The Western hero’s journey is about becoming powerful enough to change your circumstances. The isekai protagonist’s journey is about getting circumstances that are changeable in the first place.

Subaru’s suffering isn’t the downside of isekai. It’s the minimum price of admission to a world where effort actually matters.

Escapism As Honest Assessment

The criticism of isekai is always that it’s pure escapism, as if that’s self-evidently bad. But escapism requires something to escape from, and maybe we should pay more attention to what that something is.

These protagonists aren’t fleeing zombie apocalypses or alien invasions. They’re fleeing normalcy. They’re fleeing the expected trajectory. They’re fleeing lives that technically work—they have homes, food, some kind of social safety net—but feel like dying slowly while everyone pretends not to notice.

The truck functions as assisted suicide because it arrives exactly when these protagonists have already made their decision but lack the means or courage to act on it. It’s the narrative formalizing what the characters have already emotionally committed to: this life is over, and whatever comes next can’t possibly be worse.

And sometimes? They’re probably right.

The genre keeps spawning new variations—villainess reincarnation, smartphone summons, gamer systems—but the truck stays. It’s too honest to retire. It acknowledges what the narratives understand even if polite society won’t: that some lives feel worth abandoning, that some worlds feel worth leaving, and that sometimes the only difference between suicide and salvation is whether someone else is driving.