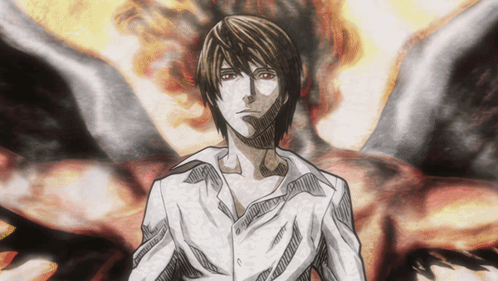

There’s a moment in episode eight of Death Note where Light Yagami, teenage serial killer and self-proclaimed god of a new world, sits at his desk surrounded by surveillance cameras. He’s being watched by the world’s greatest detective. His next move will either prove his innocence or expose him as a mass murderer. The stakes couldn’t be higher. The tension is suffocating.

And then he picks up a potato chip and announces, with the gravity of someone defusing a nuclear bomb, “I’ll take a potato chip… and eat it!”

The internet has been laughing at this scene for nearly two decades. Memes, parodies, compilations—the potato chip moment became shorthand for Death Note’s theatrical excess. But here’s the thing everyone misses while they’re busy making jokes: the scene works precisely because Death Note refuses to acknowledge how ridiculous it is. The show commits completely to its own melodrama, treating a teenager eating snacks with the same apocalyptic intensity it gives to actual murders. And that commitment—that absolute, unblinking sincerity—is exactly what makes Death Note psychologically devastating instead of accidentally hilarious.

The Potato Chip Scene: A Masterclass in Melodramatic Tension

Let’s actually examine what’s happening in this sequence. Light has convinced Ryuk to give him a piece of the Death Note small enough to hide in a bag of chips. He’s built a false compartment in his desk drawer with a miniature TV. He’s synchronized his studying with pre-recorded footage of himself studying. The cameras watching him will see him open the chips, eat them like a normal student, and keep working. What they won’t see is him watching hidden broadcasts on the tiny screen, learning the names and faces of criminals L has deliberately fed to the media as bait, and writing their names on Death Note scraps before swallowing the evidence.

It’s absurd. It’s elaborate to the point of parody. It’s the kind of plan that requires Light to have apparently spent hours engineering a chip bag with a secret compartment, all to maintain plausible deniability while eating snacks.

And director Tetsuro Araki shoots it like it’s the Normandy invasion.

The dramatic orchestral swell. The quick cuts between Light’s face, his hand reaching into the bag, L watching the monitors, the hidden TV screen flickering with victim faces. The way Light’s internal monologue narrates every micro-movement as though he’s a surgeon performing open-heart surgery. The show dedicates the same visual and auditory language it uses for actual life-or-death confrontations to a boy eating processed food.

This is where most shows would break. This is where a lesser series would give the audience a knowing glance, a small acknowledgment that yes, we’re all aware this is bonkers. A slight musical shift. A reaction shot from Ryuk that’s just a bit too comedic. Something to release the pressure valve and signal that we’re in on the joke together.

Death Note never blinks. It plays the potato chip scene with absolute poker-faced intensity, and that refusal to apologize for itself is what transforms potential comedy into genuine dread. Because if the show treated this moment as ridiculous, it would be admitting that Light’s elaborate paranoia is overkill. But Light’s paranoia isn’t overkill—he’s matched against someone who will absolutely catch him if he makes a single mistake. L has cameras in his room. L has tracked him through nothing but statistical anomalies and intuition. The potato chip scene isn’t absurd; it’s the exact level of obsessive detail required when you’re playing 4D chess with someone who thinks in five dimensions.

By treating it seriously, Death Note validates the psychological reality of the battle. This is what it actually feels like to be trapped in a room with someone who can read your heartbeat.

The God Complex Needs a Straight Face

Light Yagami believes he’s creating a perfect world. He writes names in a magic notebook and people die of heart attacks, and from this he extrapolates that he is justice incarnate, that he is reshaping human civilization, that he is becoming the god of a new world order.

He’s seventeen years old.

The entire premise requires you to take seriously the internal logic of a teenager with a god complex and a supernatural murder weapon. If Death Note ever stepped back and examined how ludicrous that sounds, the whole structure collapses. Light isn’t a mastermind because he’s objectively correct about his divine mission—he’s a mastermind because he’s committed to the bit so thoroughly that he’s outmaneuvering international law enforcement and the world’s greatest detective. His absolute conviction is what makes him terrifying.

The show’s sincerity mirrors Light’s psychology. He doesn’t see himself as a kid playing with a magic notebook; he sees every action as a calculated move in an existential war. When he eats that potato chip, he’s not being dramatic for the sake of it. In his mind, this is genuinely life or death. The cameras are watching. L is watching. One inconsistency in his behavior, one moment where he checks a name or writes in the Death Note when he should be studying, and it’s over.

The melodrama isn’t excess—it’s accuracy. This is genuinely how someone with Light’s personality would experience this situation. The world has narrowed to the space between surveillance and execution, and every choice is a tightrope walk over an abyss.

The show matches his intensity beat for beat because to do otherwise would be to undermine the central conceit: Light isn’t crazy. He’s just operating in a reality where the stakes actually justify the paranoia.

Sincerity as Psychological Suffocation

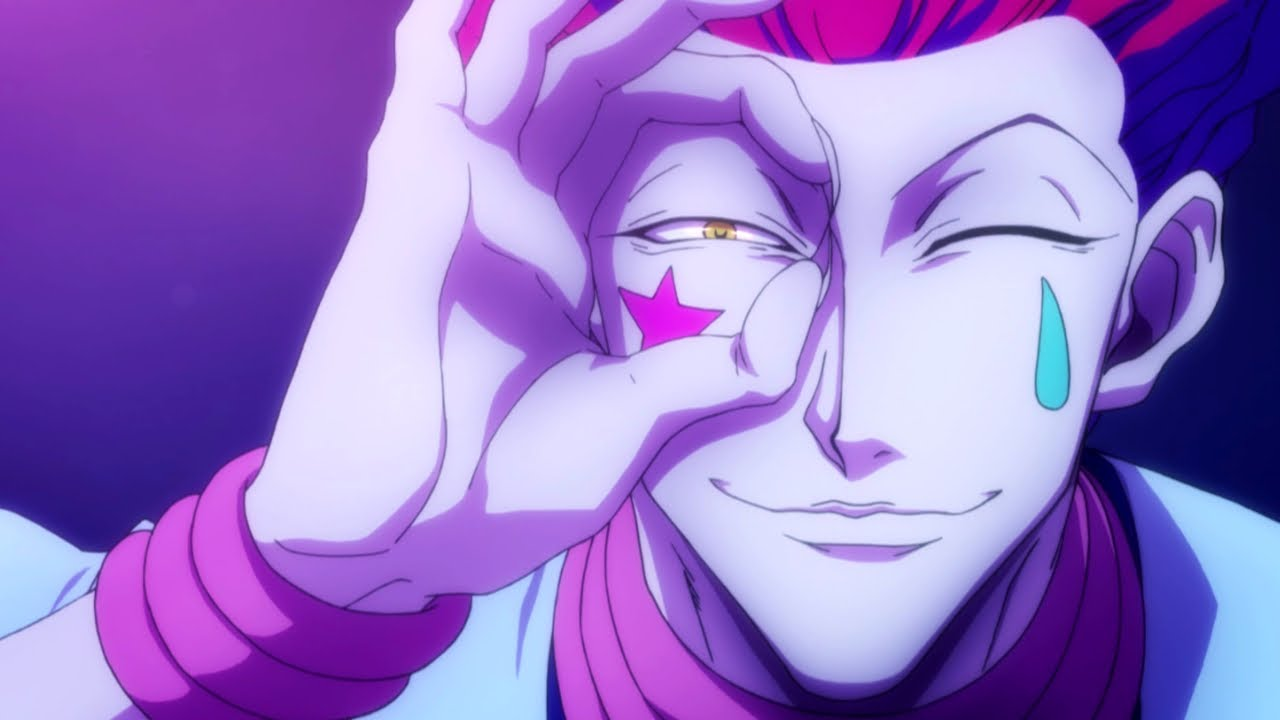

There’s a reason Death Note feels exhausting to watch. Not in a bad way—in the way that holding your breath underwater feels exhausting. The show never gives you permission to relax. It never breaks tension with comic relief or tonal shifts. Even the moments with Ryuk, who is theoretically the comedic foil, play ambiguously. Is he joking? Is he bored? Is he genuinely amused by human suffering? You’re never quite sure, and the uncertainty keeps the pressure on.

Compare this to almost any other thriller anime. Code Geass, which is basically Death Note’s flashier cousin, regularly undercuts its own drama with fanservice, slapstick school comedy, and over-the-top robot battles that border on camp. It’s still compelling, but it breathes. It gives you outs. Death Note doesn’t. Every episode is a vice grip tightening.

The famous confrontation in episode twenty-five, “Silence,” has Light and L sitting together eating cake and discussing philosophy while mentally trying to murder each other. The scene is quiet, almost mundane. They’re just two young men having dessert. And it’s more tense than most action sequences because the show has trained you to understand that nothing in Death Note is ever just what it appears to be. The cake is a strategy. The silence is warfare. L’s fork pausing mid-air might be a tell. Light’s smile might be too practiced.

By never releasing tension, never acknowledging that any of this might be somewhat silly, the show creates a suffocating sense of paranoia that mirrors what it must be like to actually be Light or L. There is no off-switch. There is no moment where you’re not calculating, not performing, not aware that one wrong move ends everything.

The potato chip scene is the perfect distillation of this: Light cannot even eat a snack without it being a calculated performance. And because the show treats this with complete seriousness, you feel the weight of that reality. The inability to ever just be anything except a carefully constructed facade.

That’s not ridiculous. That’s psychological horror.

The Economics of Perfectionism: Death Note as Post-Bubble Anxiety

Death Note premiered in 2006, but the manga launched in 2003, and understanding its cultural context explains why its particular flavor of obsessive perfectionism resonated so deeply with Japanese audiences.

The 1990s bubble economy collapse left Japan in a decades-long period economists call the “Lost Decade” (which became the Lost Twenty Years, and is now the Lost Thirty Years, because Japan’s relationship with economic stagnation is basically a long-term marriage at this point). The generation that came of age during this period—Light’s generation—inherited a cultural framework that promised success through perfect execution, but an economic reality where even perfect execution didn’t guarantee anything.

The Japanese education system’s focus on entrance exams, where a single test can determine your entire life trajectory, creates an environment where teenagers genuinely do experience every action as potentially destiny-altering. Light is the perfect student, the model son, the one who did everything right—and what does that get him in this new economic reality? The same diminishing returns as everyone else.

Enter the Death Note. Suddenly, perfect execution does guarantee results. Write a name correctly, picture the face clearly, and the target dies exactly as specified. It’s a system that actually works the way the cultural mythology said Japan worked. Effort equals outcome. Planning equals success. Precision equals control.

This is why Light’s elaborate schemes resonate beyond just being clever thriller plotting. They’re a fantasy of control in a society that spent the 90s and early 2000s learning that you can do everything right and still lose. The potato chip scene’s obsessive attention to detail isn’t just character work—it’s cultural anxiety made manifest. Light cannot afford a single mistake because he’s internalized a worldview where single mistakes are catastrophic, where there is no safety net, where perfection is the only defense against chaos.

And the show’s refusal to treat this as excessive or neurotic? That’s recognizing that for many in the audience, this level of pressure isn’t an exaggeration. It’s Tuesday.

The sincerity of Death Note’s melodrama validates the stakes its audience already feels. It doesn’t mock the idea that eating a potato chip could require strategic planning—it understands that when you’re operating in a system where one error cascades into disaster, everything requires strategic planning. Even snacks. Especially snacks, if someone’s watching.

What Irony Would Have Destroyed

Imagine if Death Note had winked at the audience. Imagine if there was a moment—just one—where the show acknowledged that a teenager with a magic murder notebook taking himself this seriously was perhaps a bit much. A meta-joke. A slight tonal shift. Anything that signaled we’re all watching the same slightly absurd spectacle together.

It would have eviscerated the show’s power completely.

Because Death Note’s entire thesis is that Light and L are both right to take this as seriously as they do. The stakes are this high. The battle does justify this level of obsession. These aren’t two people being ridiculous; these are two people operating at the absolute apex of what human intelligence and will can achieve when pushed to existential limits.

The moment the show admits that maybe all this intensity over a potato chip is a bit silly, it admits that maybe Light’s quest is silly. Maybe L’s investigation is silly. Maybe the whole premise—that a high school student could challenge the world through sheer intellect and a supernatural notebook—is silly.

And if that’s silly, then what are we doing here? Why are we investing in this story? Why do we care who wins?

The sincerity is what sells the premise. It’s what allows you to take seriously a show about a teenager murdering people with a magic notebook while being hunted by a detective who sits weird and eats candy. Remove the sincerity and you get a parody of Death Note, not the actual thing.

Look at the show’s most powerful moments: Light’s laughter after the first kill, the chain scene where he and Misa are handcuffed together, L’s death, Light’s final moments in the warehouse. None of these work if the show has been giving you permission to view any of this as camp. They work because Death Note has spent its entire runtime building a world where these emotional peaks are earned through absolute commitment.

The potato chip scene is a test. If you can accept that scene at face value, if you can watch it and feel tension instead of laughter, then you’ve accepted Death Note’s fundamental contract: we’re playing this completely straight, and if you’re willing to meet us there, we’ll give you one of the most intense psychological thrillers in anime.

The show needs you to believe that eating a potato chip can be an act of warfare, because once you believe that, you’ll believe everything else. And everything else is worth believing.

Why the Memes Miss the Point

The irony is that the potato chip scene became a meme precisely because it works. People mock it because it’s so committed to its own intensity that it becomes startling—a moment where the show’s complete sincerity crosses into something that feels almost surreal. But that’s not a flaw in the execution. That’s the execution working exactly as intended.

Death Note is a show about people who can never stop performing, never stop calculating, never allow themselves a moment of genuine unselfconsciousness. Light eating a potato chip while simultaneously watching a hidden TV, writing names in a concealed Death Note, and maintaining perfect acting for surveillance cameras isn’t ridiculous. It’s the logical endpoint of the show’s central premise: what does it look like when someone is forced to weaponize every single moment of their existence?

It looks exactly like that scene. And it should make you uncomfortable. The fact that it’s become a joke says more about our discomfort with sincerity than it does about the scene’s quality.

Death Note never apologizes for being exactly what it is: a melodramatic, operatic, absolutely sincere exploration of what happens when two geniuses try to destroy each other using nothing but their minds. It doesn’t need your permission to be intense about potato chips. It knows what it’s doing.

And that unwavering confidence in its own absurdity is precisely what makes it brilliant.