Most time travel stories fall apart the moment you think about them for more than five minutes. Characters zip through decades like they’re changing subway lines, causality becomes a suggestion, and by the end you’re supposed to just accept that love conquers thermodynamics or whatever.

Steins;Gate doesn’t do that.

Instead, it builds its entire narrative architecture on terminology borrowed from theoretical physics, treats causality like the unforgiving bastard it is, and then traps its protagonist in a nightmare constructed from his own cleverness. The show uses D-mails—text messages sent to the past via microwave-induced kerr black holes—to explore bootstrap paradoxes, worldline theory, and the Many-Worlds Interpretation with more internal consistency than most science fiction bothers to attempt. When Okabe Rintaro finally understands what he’s done, the rules don’t bend to give him an easy out.

They tighten like a noose.

This isn’t time travel as wish fulfillment. It’s time travel as consequence engine, where every attempt to fix something breaks something else, and the universe maintains its causality through sheer mathematical brutality.

The D-Mail System: Microwaves, Black Holes, and Messages to Yesterday

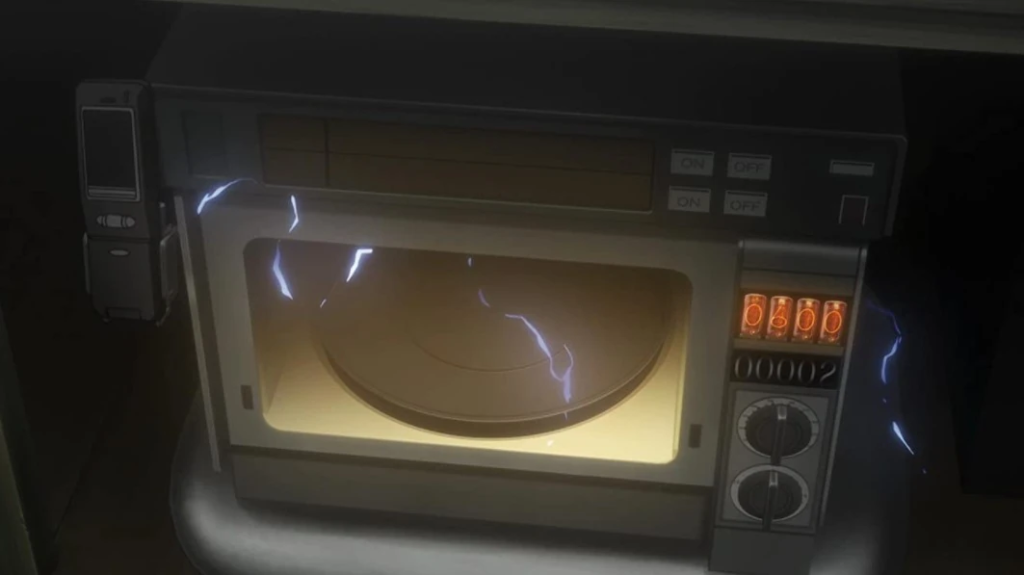

The Phone Microwave (name subject to change) sounds like something a teenager would invent in a fever dream, and that’s essentially what it is. Okabe’s malfunctioning microwave-phone hybrid can send text messages into the past by compressing data and firing it through a micro black hole similar to a Kerr black hole—a rotating black hole with a ring singularity that theoretically allows for closed timelike curves.

The Kerr metric is real physics, proposed by Roy Kerr in 1963 as a solution to Einstein’s field equations. A rotating black hole’s ring singularity could theoretically permit closed timelike curves without crossing an event horizon in the mathematics, though these regions are almost certainly physically unstable and destroyed by quantum effects in any real scenario.

Steins;Gate borrows this terminology to create a system that sounds grounded in general relativity while operating on entirely fictional rules.

The show’s approach is to use scientific language as scaffolding for its time travel mechanics rather than claiming the mechanics themselves would actually work. It’s speculative fiction that respects the vocabulary of physics even as it violates the actual constraints. The result is a time machine that feels grounded enough to be unsettling, even if you know it couldn’t exist.

When Okabe sends his first D-mail by accident, it rewrites history without fanfare. Mayuri’s Metal Upa charm becomes a plastic one. The timeline shifts—what the show calls a “worldline” change—and Okabe is the only person who remembers the previous version because of his Reading Steiner ability.

That ability is the show’s one purely narrative concession, and it transforms Okabe from observer into prisoner.

Bootstrap Paradoxes and Self-Causing Loops

Here’s where things get philosophically unpleasant: several items and pieces of information in Steins;Gate have no origin point. They exist because they will exist, trapped in self-fulfilling causal loops that make linear time look quaint.

The Metal Upa is the most obvious example.

In the Alpha worldline, Mayuri owns a metal version of the toy. Okabe sends a D-mail that prevents Mayuri from obtaining it, shifting them to a worldline where she has the plastic one instead. But later revelations show the metal Upa only existed because of time travel interference in the first place—it’s an object that exists solely because someone from the future ensured it would exist. Where did the first one come from? Nowhere. It’s information without origin, a bootstrap paradox named after the absurd notion of pulling yourself up by your own bootstraps.

The show leans into this discomfort rather than explaining it away.

Suzuha’s time machine—a modified future-SERN device disguised as a satellite dish on top of the Radio Building—is another bootstrap. Her presence in 2010 is caused by events that haven’t happened yet, and those events only occur because she traveled back to prevent them. Remove any link in the chain and the entire structure collapses, but the structure already exists, so it can’t collapse. Causality doesn’t break; it just forms a loop so tight you can’t see the seam.

This is why Okabe’s attempts to save Mayuri fail approximately 100,000 times.

He’s not fighting fate or destiny or narrative inevitability. He’s fighting mathematical convergence in a deterministic system. The Alpha worldline—the cluster of timelines where SERN achieves dystopia—has a fixed convergence point: Mayuri’s death on a specific date. No matter what Okabe changes, causality routes around his interference like water flowing around a stone. Different cause, same result. Truck hits her. Heart failure. Stray bullet. The method varies; the outcome converges.

It’s not tragedy. It’s topology.

Worldlines, Divergence Numbers, and the Illusion of Choice

Steins;Gate’s cosmology creates its own fictional framework where every possible timeline exists as a potential worldline, but only one is “active” at any given moment based on divergence from a central attractor field. Think of worldlines as parallel railway tracks: you can switch between them, but certain tracks all lead to the same station.

The Alpha attractor field leads to SERN dystopia and Mayuri’s death. The Beta attractor field leads to World War III and Kurisu’s death. Okabe switches between individual worldlines within these fields every time a D-mail changes the past, but he can’t escape the attractor field’s gravitational pull without sufficient divergence—a difference of at least 1% from the field’s baseline.

This framework uses terminology from Hugh Everett’s Many-Worlds Interpretation (1957) and concepts from chaos theory’s attractor basins, but creates its own rules that don’t actually match either system. It’s a fictional cosmology that borrows scientific vocabulary to build internal consistency rather than claiming to represent how quantum mechanics or relativity actually work.

And it’s determinism wearing the mask of free will.

Okabe’s Reading Steiner ability lets him remember worldline shifts, which sounds like a superpower until you realize it means watching everyone you care about forget conversations you had ten minutes ago. He’s the only continuous consciousness in a sea of overwritten memories, screaming into a void where nobody remembers what he’s trying to prevent.

The show never explains why Okabe has this ability. It’s presented as statistical anomaly—some people’s brains resist timeline overwriting better than others—but functionally it exists to make him suffer. He gets to keep score while everyone else enjoys the mercy of ignorance.

SERN, CERN, and Weaponized Particle Physics

The real CERN—the European Organization for Nuclear Research—spent the early 2000s being accused by random internet conspiracy theorists of trying to create black holes that would devour the Earth. The Large Hadron Collider (LHC), which came online in 2008, smashes particles at near-light speed to probe fundamental physics, and some people convinced themselves this would punch holes in spacetime.

It didn’t.

But Steins;Gate takes that anxiety and runs with it. The fictional SERN successfully creates micro black holes, discovers time travel, and uses it to establish a techno-dystopia where human experimentation and thought police are standard operating procedure. They’ve been kidnapping people to test time travel on for years, turning them into gelatinous piles of biology when the experiments fail.

The show’s dystopian future is deliberately vague—we see it through Suzuha’s descriptions and Okabe’s horror rather than extended world-building—which makes it more effective. The details don’t matter. What matters is that Okabe’s innocent tinkering with microwaves has drawn SERN’s attention, and they will use his research to accelerate their timeline of oppression.

Every innovation contains the blueprint for its own abuse.

The real-world context matters here. Steins;Gate the visual novel released in 2009, just as the LHC was making headlines and global recession was crushing Japan’s economy. The story’s paranoia about scientific institutions and shadowy organizations reflects a cultural moment when trust in large-scale systems—financial, governmental, scientific—was cratering. SERN isn’t just an evil organization. It’s what happens when pursuit of knowledge divorces itself from ethical constraint and gets backed by unlimited funding.

Okabe fights this with a microwave, a flip phone, and increasingly desperate creativity. He’s outmatched by every possible metric.

John Titor and the Fiction That Became Fiction

One of Steins;Gate’s smartest moves is incorporating John Titor, the actual internet time traveler who posted on forums between 2000 and 2001 claiming to be from 2036. The real John Titor described his mission (retrieving an IBM 5100 computer to debug legacy systems), his time machine (a Tipler cylinder-based device installed in a 1967 Chevy), and a future involving American civil war and nuclear exchange.

It was an elaborate hoax, obviously. But a compelling one.

Steins;Gate makes Titor real within its universe—specifically, makes Suzuha Amane adopt the identity to gather intelligence in the past. She posts on @channel (the show’s stand-in for 2channel, Japan’s largest anonymous forum) using Titor’s prophesies as cover, which means Okabe the obsessive conspiracy theorist has been accidentally communicating with his future colleague through an internet legend.

The IBM 5100 detail is particularly elegant. The real John Titor claimed this specific computer had an undocumented feature allowing it to debug and emulate IBM mainframe code from the 1960s-70s. This is actually true—engineers confirmed the 5100 has hidden emulation capabilities. Steins;Gate uses this verified detail to anchor its fiction, making the IBM 5100 essential for hacking SERN’s database.

Fiction borrowing from fiction that borrowed from reality creates a three-layer recursion that feels appropriate for a show about time loops.

The real John Titor mystery was never solved. Whoever created the hoax understood enough physics to sound credible and enough sociology to make the future sound plausible. Steins;Gate treats this unknown person’s creative work with respect, incorporating the mythology whole rather than cherry-picking convenient details. It’s fiction in conversation with fiction, both using time travel to explore anxiety about the future.

The Tragedy of Okabe Rintaro: Consciousness Trap

By the midpoint of the series, Okabe has lived through more failed timelines than most people live days. He’s watched Mayuri die in dozens of configurations—sudden, slow, random, targeted—and discovered that his attempts to save her only redistribute the tragedy to different victims. The universe maintains its balance through substitution.

Save Mayuri in the Alpha worldline? You’re still in the Alpha attractor field. She dies anyway, just differently.

Escape to Beta by preventing her death entirely? Kurisu dies instead, and the world descends into war.

The show’s central horror isn’t the time travel mechanics. It’s the realization that having perfect information doesn’t grant power—it grants responsibility you can’t fulfill. Okabe knows exactly what will happen and exactly how helpless he is to change the outcome. He’s not fighting fate; he’s reading the results of an equation he’s trapped inside.

This transforms his mad scientist persona from quirky affectation into psychological defense mechanism. The chunibyo antics—calling himself Hououin Kyouma, declaring himself at war with shadowy organizations, maintaining his character even when alone—are how he avoids processing the weight of his knowledge. If he treats everything as theatrical performance, maybe it won’t hurt as much when people die.

It hurts anyway.

The show never explicitly states this interpretation, but it’s communicated through performance. Mamoru Miyano’s voice acting shifts between the manic energy of Hououin Kyouma and Okabe’s genuine desperation so smoothly that you can hear the mask cracking in real-time. When he finally breaks—when the facade can’t hold anymore—he doesn’t become a different character. He becomes the person who was always underneath, exhausted and terrified and completely out of options.

Reading Steiner stops being a gift approximately fifteen timelines in. After that, it’s just a detailed record of every failure, accessible in perfect clarity whenever he closes his eyes.

Operation Skuld and the Steins Gate Worldline

The solution to Okabe’s nightmare is so absurd it circles back to brilliant: he has to fake Kurisu’s death perfectly enough to fool his past self, thereby preventing the D-mail that triggered the Beta worldline chain while maintaining the causal structure that led to the solution. He needs to save her without saving her, changing the outcome while preserving the observation.

This requires stabbing the woman he loves non-fatally, timing it precisely to match his own memories of discovering her body, and hoping his past self doesn’t notice the difference between “bleeding out” and “covered in blood but alive.”

It’s time travel solution as theater production. The physics matter less than the performance.

The Steins Gate worldline—divergence 1.048596%—exists in the narrow band between Alpha and Beta attractor fields where neither Mayuri nor Kurisu die and SERN never achieves dystopia and World War III never ignites. It’s not that these outcomes become impossible; it’s that divergence pushes them beyond the convergence horizon. They’re still mathematically possible futures, just no longer gravitationally inevitable.

Getting there requires Okabe to trust that deceiving himself is possible, which might be the show’s final statement on determinism: even in a universe where causality is rigid and convergence points exist, human consciousness is slippery enough to exploit the gaps. Not through strength or genius, but through theater and coincidence and bleeding exactly the right amount.

The Steins Gate worldline isn’t discovered or calculated. It’s performed into existence.

The Weight of Remembering

Here’s what stays with you after Steins;Gate ends: Okabe is the only person who remembers the other timelines. Mayuri doesn’t know about the hundred times she died. Kurisu doesn’t remember being killed or erased from existence. Daru never learned his daughter would become his colleague through time travel. The lab members live in the Steins Gate worldline with normal memories of a normal timeline where nothing terrible happened.

Okabe remembers all of it.

He carries every failed attempt, every death, every version of people he loved who no longer exist in this configuration of reality. Those worldlines are gone—erased when the active timeline shifted—but he lived through them. He watched Mayuri’s clock stop over and over. He erased Kurisu from existence to save someone else. He experienced months of subjective time that never occurred in the worldline everyone else inhabits.

The show doesn’t dwell on this. It ends on hope and reunion, the lab members together again, the future open.

But Okabe exists in the Steins Gate worldline knowing exactly how many attempts it took to get here, how many variations of his friends ceased to exist to make this one possible. He understands better than anyone that this specific confluence of events—this precise divergence value, this exact sequence of choices—was never guaranteed.

He knows how easily it could have been different.