There’s a special category of anime that operates like a slow-acting poison. You sit down expecting gentle vibes and tea-making montages, and several episodes later you’re staring at the ceiling wondering why a show about literally nothing made you question the entire trajectory of your life. These aren’t your standard tearjerkers that announce their emotional devastation with swelling orchestras. These are the quiet ones. The patient ones. The shows that understand the difference between boring and empty—and weaponize that gap with surgical precision.

The Art of Disguising Devastation as Daily Life

Girls’ Last Tour presents itself as two girls riding a vehicle through ruins, eating potatoes, and discussing the texture of rations. Chito reads books. Yuuri eats everything in sight. They sing off-key. They argue about whether fish have feelings. The show’s visual language is so aggressively mundane—flat horizons, geometric rubble, muted colors—that calling it “post-apocalyptic” feels like giving it too much credit. It’s post-post-apocalyptic. Humanity already had its dramatic ending. This is the part where the universe files its paperwork.

But then Episode 6 happens. The library episode. Chito and Yuuri find a massive archive—humanity’s preserved knowledge—and immediately start burning books for warmth. Not in some dramatic revolutionary gesture, but because they’re cold and books burn. The show doesn’t editorialize. It doesn’t have characters give speeches about the tragedy of lost knowledge. It just shows you two children committing cultural extinction with the same casual energy they’d use to peel potatoes. The real devastation is how reasonable it feels. You’re watching the death of human civilization and thinking, “Yeah, warmth is probably more useful than Kant right now.”

This is the fundamental trick: using slice-of-life’s structural emptiness as a Trojan horse for existential terror. The format trains you to expect nothing, so when something profound appears, it doesn’t arrive as dramatic revelation—it simply exists, unavoidable and unadorned, like finding a spider in your shoe.

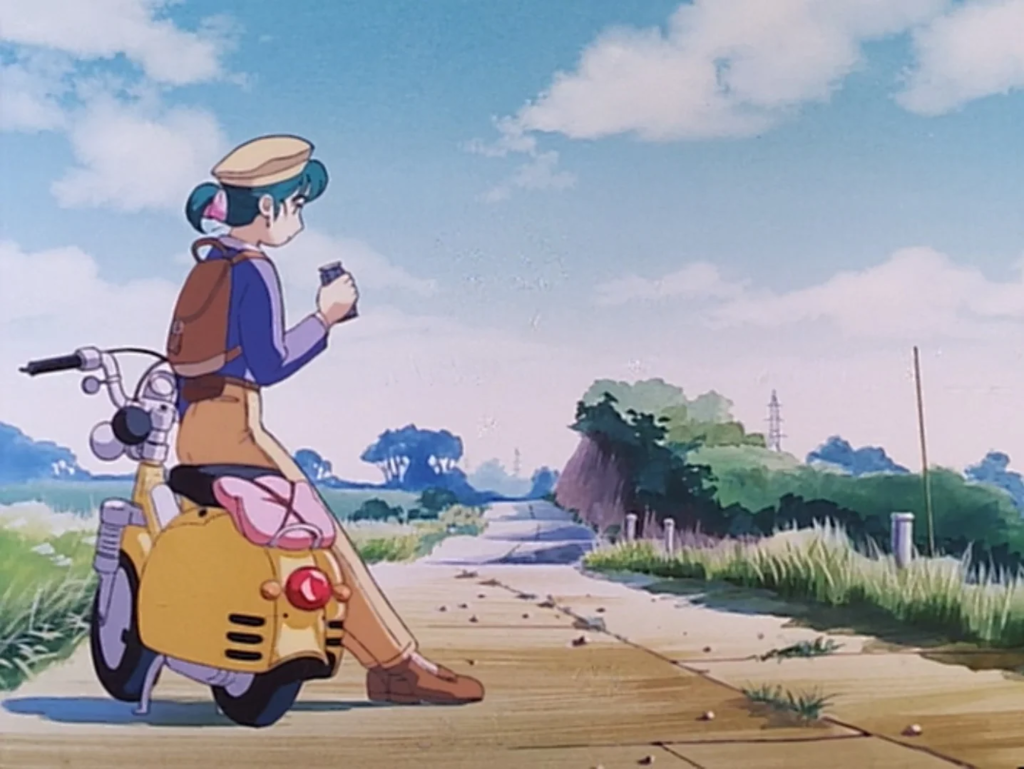

Yokohama Shopping Log and the Economics of Ending

Yokohama Kaidashi Kikou takes this approach and pushes it into deeply uncomfortable territory disguised as healing. Alpha is an android running a coffee shop in a slowly drowning world. The ocean is rising. Humanity is disappearing. Tokyo is becoming Venice, except sadder and with fewer tourists. And Alpha just… makes coffee. Takes photographs. Rides her scooter. The manga and OVAs spend their runtime on Alpha adjusting a camera’s aperture or the precise angle of afternoon light through cafe windows.

The series functions like a meditation on acceptance that would make a Buddhist monk uncomfortable. Because what Alpha is accepting isn’t just personal mortality—she’s an android, she’ll outlast humanity by centuries—but the complete irrelevance of that fact. She’s accepting that existence doesn’t require purpose, that beauty doesn’t need an audience, that a perfect cup of coffee matters exactly as much on the last day of human civilization as it did on the first. It’s slice-of-life as philosophical surrender, and it’s packaged in imagery so gentle you might miss that you’re watching grief without the object of grief, mourning that’s already moved past denial and bargaining straight into the acceptance stage and set up a small business there.

The show’s refusal to dramatize creates this suffocating intimacy. When Alpha visits another android who’s slowly breaking down, the scene is framed like visiting an elderly relative in hospice. No robot battles. No desperate searches for repair parts. Just two artificial beings having tea while acknowledging that obsolescence isn’t a problem to solve—it’s a condition to experience. The mundanity is doing the heavy lifting because the mundanity is the point. Life continues right up until it doesn’t, and the transition is quieter than you’d expect.

Haibane Renmei: Purgatory Requires Proper Filing

If Haibane Renmei were honest about its genre, nobody would watch it. “Fantasy series about afterlife processing” doesn’t sell itself. So instead, it presents as a show about winged people in a walled city doing laundry, working at a clock tower, and managing thrift shops. Look at these angel-like beings doing taxes! Watch them argue about jacket sizes! See them sweep floors!

Then the show quietly reveals that the entire setting is purgatory, every character is working through unresolved trauma from their deaths, and the “Day of Flight” is either transcendence or oblivion depending on whether you’ve adequately confronted your sins. The wall around their city isn’t protection—it’s containment. The halos aren’t holy—they’re markers. And those mundane jobs aren’t just employment; they’re therapy disguised as economics, keeping damaged souls occupied while they unconsciously work through whatever killed them.

Rakka’s arc is particularly brutal in its understatement. She arrives with no memory, gets her wings (painfully), receives her halo, and starts integrating into daily life. The show spends multiple episodes on her just… adjusting. Learning the rules. Finding work. Making friends. Pure slice-of-life tedium. Except every mundane interaction is actually her processing complex feelings about suicide and self-worth, and the show never explicitly confirms this until you’ve already internalized it through symbolism so subtle you could write it off as aesthetic choice.

When Reki’s crisis finally surfaces in the later episodes, the revelation that she’s been stuck in this liminal space for years, unable to move forward, transforms every previous scene of her smiling and making art into retroactive horror. The slice-of-life wasn’t preparation for the drama—the drama was always there, just filed under “daily routine” where you wouldn’t think to look for it.

The Economic Malaise Behind the Mundane

Here’s where these shows stop being coincidental and start being symptomatic. The rise of contemplative, heavy slice-of-life anime maps almost perfectly onto Japan’s Lost Decades—the period of economic stagnation following the asset bubble collapse in the early 1990s. When an entire generation’s economic expectations implode, when the promise of perpetual growth reveals itself as temporary fantasy, when “try harder” stops correlating with “succeed more,” cultural output gets weird.

Traditional narratives require forward momentum—heroes achieve goals, hard work pays off, sacrifice leads to victory. But what happens to storytelling when an entire society collectively realizes that momentum might be a lie? You get shows where the point isn’t achieving anything. Where existence without progress becomes not failure, but simply existence. Where the absence of dramatic arc isn’t poor writing but accurate representation of how most lives actually unfold: slowly, repetitively, with profound moments hiding inside mundane ones like splinters you don’t notice until later.

Mushishi exemplifies this perfectly. Ginko wanders a historical Japan where supernatural phenomena (“mushi”) exist at the margins of human perception, causing problems that can’t be solved with effort or willpower—only understood, managed, or accepted. Each episode is functionally: person has problem, Ginko shows up, Ginko explains the problem, situation resolves itself or doesn’t. There’s no power scaling. No training arc. No collecting increasingly powerful mushi to battle the final boss mushi. Just an endless cycle of humans encountering forces beyond their control and learning to adapt.

The show’s episodic structure mirrors economic stagnation perfectly. No episode’s events carry forward. Each village is isolated. Progress resets. Ginko never accumulates wealth or status. He just… continues. Walking from problem to problem, smoking his cigarettes, explaining that sometimes nature is indifferent to your suffering and the best you can do is find a way to coexist with that indifference. It’s the most Japanese show imaginable: beautiful, melancholic, and deeply invested in the idea that acceptance beats ambition when reality refuses to cooperate with your plans.

Compare this to the bombastic shonen boom of the 1980s—Dragon Ball, Saint Seiya, Fist of the North Star—all products of Japan’s bubble economy, when infinite growth seemed plausible and testosterone could solve any problem with sufficient volume and hair gel. The shift to contemplative slice-of-life isn’t artistic evolution; it’s cultural adjustment. When your economy stops promising futures, your stories stop assuming them.

Aria’s Weaponized Gentleness

Aria the Animation might be the most dangerous entry in this category because it’s actually healing and gentle and does genuinely want you to feel better—but it achieves this through what amounts to emotional hostage negotiation. Set on terraformed Mars (renamed “Aqua”), the series follows gondoliers-in-training in Neo-Venezia, a recreation of Venice designed for tourism in humanity’s space-faring future. Everything is picturesque. Everyone is kind. Conflicts resolve through understanding. The worst thing that happens is someone being slightly sad about weather.

But the show’s entire emotional architecture rests on impermanence. Every episode is about the transitory nature of moments, the inevitability of change, the melancholic beauty of things that cannot last. Akari’s journey isn’t just about becoming a professional gondolier—it’s about consciously experiencing each moment while knowing it’s already becoming memory. The show’s obsessive focus on seasonal changes, on appreciating “wonderful things,” on the phrase “ara ara” as mantra, is teaching mindfulness to people who need it because their present is already dissolving into past tense.

President Aria (the cat) is effectively a Buddhist koan in animal form. He doesn’t communicate. He doesn’t solve problems. He simply is, perfectly content in each moment, and somehow this fat alien cat becomes the show’s spiritual center. The message is uncomfortably clear: human anxiety about meaning and purpose is a cognitive error. The cat has it right. Just exist. Find this emotionally comforting, we dare you.

The finale of the series makes this explicit by having its characters literally age out of the gentle present the show has constructed. Akari becomes a full Prima, her training ends, and the eternal present of Neo-Venezia’s seasons continues without her student status to anchor it. The show isn’t sad about this. It presents growth and change as natural and good. Which somehow makes it worse. You’re being told that everything you’ve come to love about these 52 episodes was always temporary by design, and that’s beautiful, and you should accept this, and if you’re crying about it that just means it worked.

This is slice-of-life as spiritual manipulation, and it’s effective precisely because it never raises its voice.

March Comes in Like a Lion and Depression’s Daily Schedule

Sangatsu no Lion (March Comes in Like a Lion) takes a more direct approach: protagonist Rei Kiriyama is obviously, clinically depressed from episode one. Orphaned, isolated, using shogi as simultaneous coping mechanism and self-punishment. The show doesn’t hide this. But what it does do is bury the processing of that depression under an avalanche of mundane moments with the Kawamoto sisters—cooking, eating, New Year’s preparations, solving minor domestic problems.

The visual language splits between Rei’s segments (dark, geometric, suffocating) and the Kawamoto household scenes (warm, fluid, organic). The contrast is the point. Depression isn’t fought through dramatic confrontation but through the accumulation of small, kind moments that gradually make existence slightly less unbearable. Rei doesn’t have a breakthrough episode where he’s suddenly healed. He just slowly becomes someone who can tolerate being alive, one bland meal with the sisters at a time.

The show’s most devastating scenes are the quiet ones. Rei sitting alone in his apartment, the camera lingering on empty space. Rei walking through crowds, visually isolated. Rei winning shogi matches with the emotional investment of someone filing paperwork. The slice-of-life format forces you to experience depression’s actual rhythm: not dramatic spirals, but endless flat days where nothing particularly bad happens but nothing feels worth the effort either.

When the Kawamoto sisters’ storyline introduces genuine trauma—particularly Hina’s bullying arc—the show maintains its mundane framing even through intense emotional territory. Bullying isn’t presented as dramatic confrontations but as daily erosion. Each small cruelty is framed like the show frames making tea or walking to school. The horror is in the repetition, the ordinariness, the way violence becomes routine. Slice-of-life structure transforms from gentle framing to suffocation device. Every peaceful domestic scene now carries the weight of knowing it’s temporary shelter from ongoing psychological warfare.

The Mathematics of Nothing

What these shows understand is that “nothing happens” is relative. In traditional narrative structure, events require deviation from status quo. Someone must die, fight, confess, transform. But in slice-of-life that’s actually doing philosophical work, the status quo is the event. Maintaining normalcy under abnormal circumstances becomes the dramatic action.

In Girls’ Last Tour, continuing to exist is the plot. In Yokohama Kaidashi Kikou, experiencing beauty while it fades is the conflict. In Haibane Renmei, performing ordinary tasks while dead is the character development. These shows aren’t slice-of-life by default; they’re using slice-of-life’s structural absence as the foundation for presence that couldn’t exist in more active formats.

It’s also worth noting how many of these shows feature explicitly non-human or semi-human protagonists: androids, angel-like beings, souls in purgatory. This creates emotional distance that makes the philosophical weight bearable. You can contemplate existence’s meaninglessness more easily when filtered through an android who literally doesn’t age or a soul who’s already died. The slice-of-life mundanity keeps you engaged while the non-human elements provide just enough separation to think about uncomfortable truths without activating self-preservation instincts.

Conclusion

The slice-of-life that isn’t operates on a simple principle: the best way to discuss unbearable things is to make them look boring. Bury existential crisis under grocery shopping. Hide grief inside tea ceremony. Present the apocalypse as extended camping trip. The format’s relaxed pacing and mundane focus aren’t limitations to work around—they’re the mechanism that makes deeper content accessible.

These shows understand something uncomfortable about human psychology: we’ll accept almost anything if it’s presented calmly enough, with sufficient attention to small beautiful details, in a context that doesn’t demand we acknowledge what we’re accepting. By the time you realize you’ve been thinking about mortality, meaninglessness, or the inevitable decay of all things, you’re already twelve episodes deep and emotionally compromised.

The “nothing happens” is doing everything. You just weren’t paying attention to where it was happening.