The scariest thing about Johan Liebert isn’t that he kills people. It’s that he doesn’t exist.

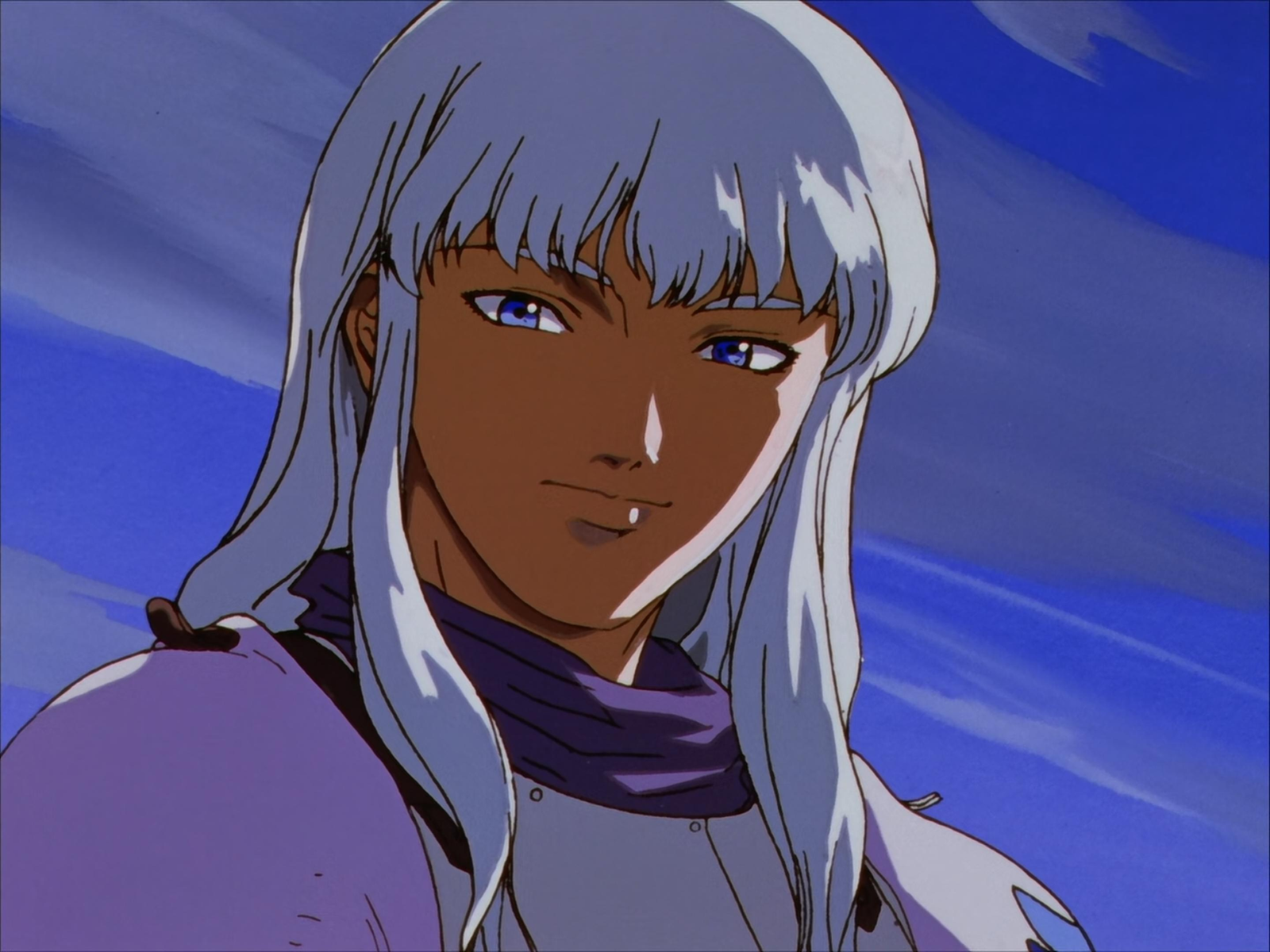

Not in the ontological sense—obviously he’s physically there, doing terrible things with those unsettling blue eyes and that smile that looks like someone practiced it in a mirror. But Johan has no core identity. He’s a walking story that different people keep writing and rewriting, and somewhere in that process, the actual person got erased. What’s left is a performance so convincing that even Johan himself seems to believe he’s the monster everyone says he is.

This isn’t about excusing murder. It’s about understanding how Monster pulls off something most psychological thrillers just gesture at: showing us someone who became evil because “evil” was the only coherent narrative available to him. Johan didn’t choose darkness because he’s a psychopath born wrong. He chose it because everyone—from Bonaparta to his mother to the people of his childhood—spent years telling him a story about who he was, and he eventually had no choice but to live inside it.

The show keeps calling back to the idea of the “nameless monster.” That’s not a metaphor. That’s a diagnosis.

The Nameless Monster Isn’t a Title—It’s a Condition

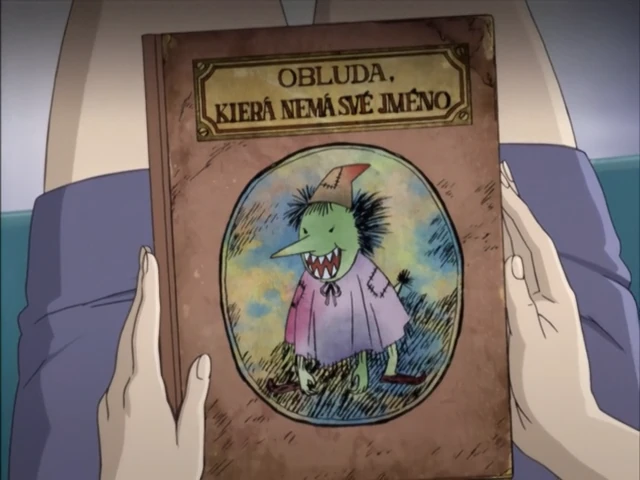

The picture book isn’t just a plot device. It’s the blueprint for Johan’s entire existence.

When Bonaparta creates “The Nameless Monster,” he’s not writing children’s literature—he’s articulating the logic that destroyed Johan’s childhood. The story follows a monster without a name who goes from town to town, becoming whatever the townspeople fear most. It eats a shoemaker and becomes a shoemaker. It eats a hunter and becomes a hunter. By the end, the monster has consumed so many identities that it can’t remember which one was originally its own.

Johan reads this book as a child and recognizes himself. Not because he’s naturally monstrous, but because he literally doesn’t have a name that stays consistent. The Liebert twins were caught in institutional systems designed to break down identity—environments where their names, their sense of self, even their gender could be swapped out depending on what was useful. When you spend your formative years being told that you’re whoever someone else needs you to be, the picture book stops being fiction. It becomes instruction.

The show reveals this through scattered memories that never quite align. Johan and Anna switching clothes and names. Their mother choosing one child over the other at the door—except both twins remember being the one chosen and the one rejected. These aren’t contradictions. They’re evidence that the twins’ identities were manipulated so thoroughly that memory itself became unreliable.

The book functions like a thematic blueprint for the identity-erasure system behind Johan’s childhood. If you’re given no consistent narrative about who you are, you’ll eventually accept whatever story gets told most loudly. And if that story is “nameless monster,” you’ll become it with terrifying precision.

When Your Mother Points at You and Says “That One,” You Become Whichever One She’s Pointing At

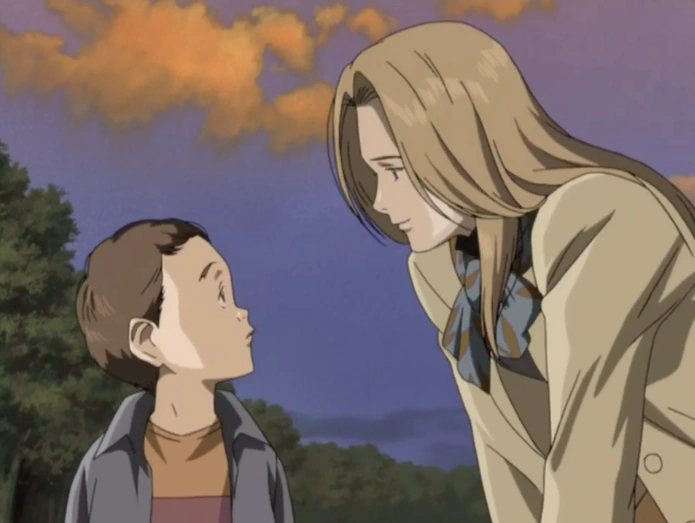

The door scene is the emotional lynchpin of the entire series, and it’s deliberately ambiguous.

Anna remembers their mother pointing at her and saying “that one,” sending Johan to die. Johan remembers their mother pointing at him. The show never confirms which memory is real—and that’s the point. The trauma isn’t about who was actually chosen. The trauma is about both children internalizing that their mother couldn’t tell them apart, that they were interchangeable, that there was no “Johan” or “Anna” substantial enough to save.

This is where Johan’s pathology crystallizes. If your own mother can’t distinguish you from your twin, if the person who should know you best in the world treats you like a role that anyone could play, then what exactly are you? The only rational response is to embrace that fungibility completely. Become nobody. Become everybody. Erase yourself so thoroughly that you can slip into any identity and make it yours.

The show draws this out through Johan’s pattern of becoming perfect reflections of what people around him expect. When he’s with Anna, he’s the protective brother. When he’s with the Lieberts, he’s the model son. When he’s with the university students, he’s the charismatic intellectual. Each performance is flawless because there’s nothing underneath contradicting it. He’s not pretending—he’s genuinely inhabiting the role because he has no competing self to maintain.

And then he destroys each identity completely, burning down the performance and everyone who witnessed it. Because if you’re nobody, the only way to prove you existed at all is through negation. Through absence. Through making sure that the only story left is the one about the monster who erases everything he touches.

That’s not evil. That’s someone who learned the wrong lesson about how to exist.

Real-World Context: The Shadow of Institutional Dehumanization

Monster is set in post-reunification Germany for a reason, and it’s not just aesthetics.

The series draws heavily on the atmosphere of Cold War-era institutional violence—the documented reality of state programs that treated human psychology as raw material to be manipulated. While the specific experiments depicted in Monster are fictionalized (Kinderheim 511, the Red Rose Mansion), they echo genuine patterns of how authoritarian systems approached identity and control.

East Germany’s infrastructure included facilities where children were subjected to psychological conditioning, ideological indoctrination, and systematic attempts to reshape their sense of self. Orphanages and state institutions operated under methods that prioritized producing compliant citizens over psychological wellbeing. The goal wasn’t always espionage—often it was simply control. Breaking down a person’s original identity and rebuilding them according to institutional needs.

The series captures something true about what happened when these systems collapsed. When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, the hasty dismantling of East German institutions left psychological wreckage: people with fragmented identities, disrupted childhoods, and no clear sense of who they’d been before the machinery of the state got hold of them. The administrative chaos meant missing records, lost documentation, identities that existed in files but nowhere else.

Johan represents the fictional embodiment of that real historical trauma—not as a literal case study, but as a meditation on what happens when institutional dehumanization outlives the political systems that created it. The show never needs to state this explicitly because it saturates every scene of his backstory: the sterile institutional settings, the calculated psychological manipulation, the erasure of the children’s original identities in service of something larger than themselves.

The monster was made, not born. And it was made by people who thought identity was just another resource to exploit.

Johan Doesn’t Want to Destroy the World—He Wants to Prove He Was Never in It

The suicide mission isn’t about nihilism. It’s about coherence.

Johan’s ultimate plan—to orchestrate his own death in a way that erases all memory of him—makes perfect sense if you understand that he’s trying to solve an identity crisis through narrative logic. If you’ve spent your entire life being whatever story people tell about you, and those stories are all contradictory and horrifying, then the only way to achieve any kind of internal consistency is to erase all the stories. To die in a way that leaves no witnesses, no records, no persistent narrative.

He tells Dr. Tenma that he wants to be the last one standing in a field of corpses, then shoot himself so there’s nobody left who remembers him. That’s not megalomania—it’s someone trying to solve the philosophical problem of a self that never cohered in the first place. If nobody remembers you, then all the contradictory narratives collapse. You achieve a kind of negative unity.

The show presents this through Johan’s systematic elimination of everyone connected to his past. He’s not just killing witnesses to crimes. He’s killing everyone who has a version of him in their head—the Johan who was a kind boy, the Johan who was a victim, the Johan who was a monster. Each murder is an attempted deletion of a story, an effort to reduce himself to zero.

Dr. Tenma disrupts this plan not by overpowering Johan, but by refusing to erase him. By saving Johan’s life even after everything, Tenma insists on writing a different story: one where Johan is human enough to be saved, complex enough to deserve continued existence despite the horror he’s caused. It’s the first time someone has told Johan a story about himself that includes the possibility of change, of future, of identity as something that can be rebuilt rather than erased.

One reading is that Johan’s breakdown in that moment—the tears, the vulnerability—reflects the first time someone refuses to reduce him to a monster, the first time someone offers a narrative that doesn’t require his own annihilation to make sense.

The Real Horror Is How Easy It Is to Make a Monster

Monster is terrifying because it’s not about innate evil.

The show spends 74 episodes demonstrating that Johan could have been anyone. Given the right childhood trauma, the right institutional manipulation, the right absence of stable identity formation, almost anyone could become what Johan became. There’s no special darkness in him, no unique pathology. He’s just someone who got caught in the machinery of narrative construction with no way to resist it.

This is why the show refuses to give us a satisfying villain. Johan isn’t defeated through superior force or moral righteousness. He’s not punished by cosmic justice. He just… continues existing, blank and empty, in a hospital bed. The horror doesn’t resolve because the conditions that created him haven’t changed. There are still systems that erase identities, still institutions that treat human psychology as raw material, still societies that need monsters to explain away their own violence.

Johan’s final mystery—his disappearance from the hospital—isn’t a sequel hook. It’s a reminder that the nameless monster is still nameless. Still capable of becoming whatever story gets told next. Still out there, because the story was never really about Johan specifically. It was about what happens when we let narrative construction replace actual identity, when we treat people as blank slates to be written on rather than complex beings to be understood.

The monster wasn’t the boy with blue eyes. It was the process that made him empty enough to reflect back whatever darkness we were already looking for.