There’s a specific kind of dread that only Studio Ghibli can pull off. Not the screaming, city-leveling kind. The quieter one. The kind that pours you tea, thanks you for your patience, and then calmly explains why your home needs to be erased for the greater good.

Ghibli doesn’t build villains like anime usually does. There are no god complexes delivered at maximum volume, no dramatic laughter echoing across the battlefield. Instead, there’s paperwork. Schedules. Policies. A soft-spoken certainty that whatever is happening is unfortunate but necessary. Which somehow feels worse.

This is the quiet cruelty of Ghibli antagonists: harm without malice, violence without spectacle, destruction carried out by people who look you in the eye and genuinely believe they’re being reasonable.

Cruelty That Thinks It’s Responsible

Take Princess Mononoke. If you go in expecting a traditional villain, you might spend the first hour confused. Nobody is cackling. Nobody is summoning demons for fun. Instead, you get Lady Eboshi, calmly explaining her vision.

Iron Town is efficient. Productive. Safe. It gives work to lepers and former brothel workers. Eboshi speaks with clarity and purpose, like someone who’s already rehearsed her defense in case the universe files a complaint. When she orders the forest burned and the gods hunted, it isn’t framed as hatred. It’s framed as logistics.

The cruelty lands not when she fires a gun at a god, but when she does it without hesitation. The scene where she shoots Nago and later targets the Forest Spirit is chilling precisely because she never doubts herself. The animation reinforces this: steady posture, steady hands, no dramatic close-up begging you to boo. She’s not cruel in spite of her morality. She’s cruel because of it.

Ghibli’s camera doesn’t flinch here. It lets you sit with the idea that harm becomes easier when it’s justified as progress. Eboshi doesn’t destroy the forest out of greed; she does it because she has a plan, and plans, once written down, demand obedience.

Bureaucracy as a Horror Genre

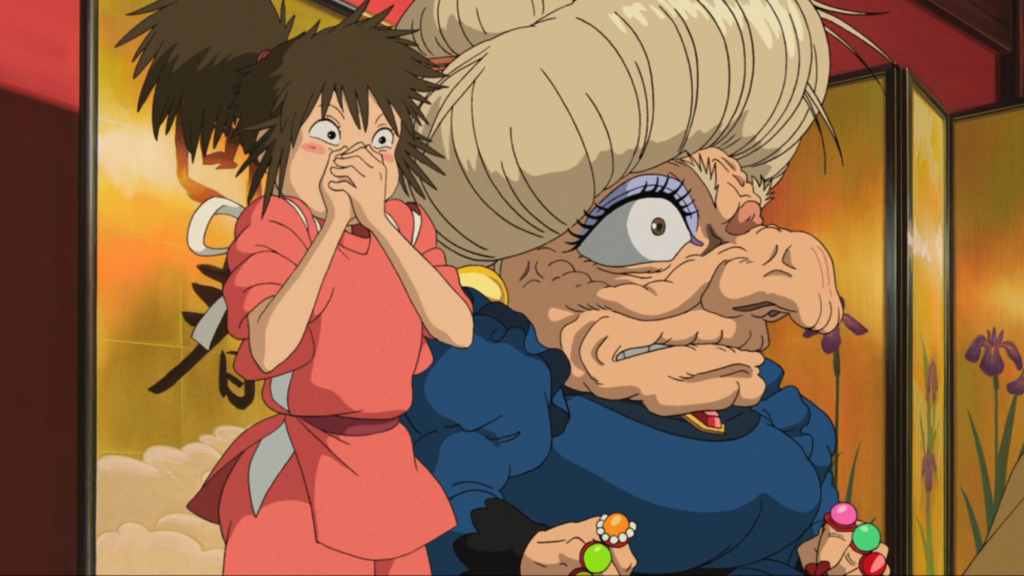

Then there’s Spirited Away, which quietly introduces one of the most unsettling antagonists in animation history: Yubaba.

Yubaba doesn’t terrorize through force. She terrorizes through contracts. The name-stealing scene—where Chihiro watches her identity reduced to a single character—is not violent in any conventional sense. No blood. No screaming. Just a signature, a stamp, and a lifetime of consequences.

Yubaba’s bathhouse runs perfectly. That’s the problem. Every rule exists for a reason. Every punishment is technically justified. The workers are overworked, exploited, and disposable, but nobody is breaking policy. When Yubaba enforces her authority, she does so like a manager explaining company guidelines with a smile that suggests she’s tired of repeating herself.

This is cruelty optimized. Efficient. Repeatable. Scalable.

The genius here is that Ghibli doesn’t frame Yubaba as chaos. She is order. And once order decides you’re expendable, there’s no villain monologue to interrupt the process. Just the sound of ink drying.

When the World Is the Problem (And Knows It)

What makes this approach hit harder is how closely it mirrors real-world systems—particularly those shaped by postwar Japanese economic realities. Hayao Miyazaki has repeatedly expressed skepticism toward unchecked industrialization and the idea that growth automatically equals good. Ghibli films absorb this worldview and translate it into narrative gravity.

In Japan’s rapid economic expansion after World War II, progress often came bundled with environmental damage, rigid corporate hierarchies, and a cultural expectation to endure quietly. Ghibli’s antagonists feel born from that atmosphere. They don’t need to be evil; they just need to keep things running.

In Princess Mononoke, the conflict isn’t man versus nature—it’s production versus consequence. In Spirited Away, labor is transactional to the point of identity erasure. These films don’t scream about capitalism or bureaucracy. They let you watch it work, which is far more uncomfortable.

The cruelty lies in inevitability. The systems function. The damage is a side effect, not a bug. And once you accept that framing, resistance starts to look irrational.

No Redemption Arc, Just Aftermath

What Ghibli refuses to do—almost aggressively—is give you the comfort of a fully defeated villain. Lady Eboshi loses an arm, not her convictions. Yubaba doesn’t change; she merely loosens her grip when it no longer benefits her. The world shifts slightly, but the machinery remains.

This is where the quiet cruelty lingers. Ghibli understands that harm doesn’t vanish with a single emotional breakthrough. It survives in institutions, habits, and well-run bathhouses. The antagonist doesn’t need to return for a sequel. Their influence already won.

The Smile That Stays With You

Ghibli villains don’t haunt you because they’re terrifying. They haunt you because they’re plausible. They sound like people who’ve thought this through. People who would apologize while ruining everything and mean it.

By refusing spectacle, Ghibli makes cruelty feel intimate and administrative, like something that could happen while everyone involved insists they’re being reasonable. And that’s why these antagonists linger long after the credits roll—not as monsters, but as reminders that the most lasting damage is often done calmly, competently, and with excellent posture.