Neon Genesis Evangelion doesn’t make sense because it’s not supposed to. The show that became anime’s most dissected text started as a mecha series and ended as its creator’s public therapy session. Somewhere between the first Angel attack and Shinji screaming in a hospital room, the plot stopped mattering and the psychology took over. The religious symbols don’t decode to anything. The Freudian imagery is window dressing. And that ending everyone argues about? It’s exactly what it looks like—a man running out of money and mental stability in equal measure.

The brilliance isn’t in solving Evangelion. It’s in recognizing that Anno Hideaki built a narrative that collapses the same way his protagonist does.

The Symbols Mean Nothing (And That’s The Point)

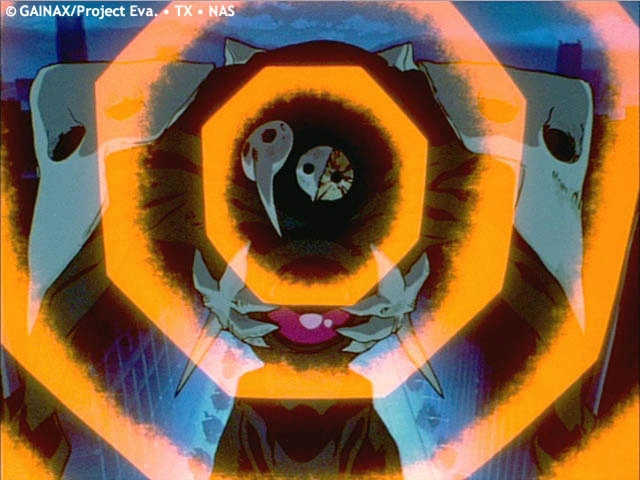

The cross-shaped explosions look profound. The Lance of Longinus, the Tree of Sephiroth, the Dead Sea Scrolls—every religious reference stacks up like evidence in a conspiracy theory. Viewers spent decades constructing elaborate theological frameworks to explain why giant cyborg monsters explode into cruciforms.

Anno admitted in a 1996 Newtype interview that the Christian imagery was chosen because “it looked cool” and “exotic” to a Japanese audience. The symbols function as aesthetic intimidation, creating the impression of deeper meaning through sheer visual density. It’s brilliant misdirection. While audiences tried to decode fake Kabbalah, the actual story was happening in the space between what characters said and what they couldn’t articulate.

The religious iconography works like a magician’s flourish—it keeps your eyes on the wrong hand while the real trick happens elsewhere.

That elsewhere is the precise anatomization of depression, social anxiety, and pathological self-loathing played out across twenty-six episodes.

The Hedgehog’s Dilemma and the Geometry of Loneliness

Ritsuko explains the Hedgehog’s Dilemma in episode four: hedgehogs want warmth but their spines wound each other when they get close. It’s presented as evolutionary biology trivia. It’s actually the thesis statement for every relationship in the series.

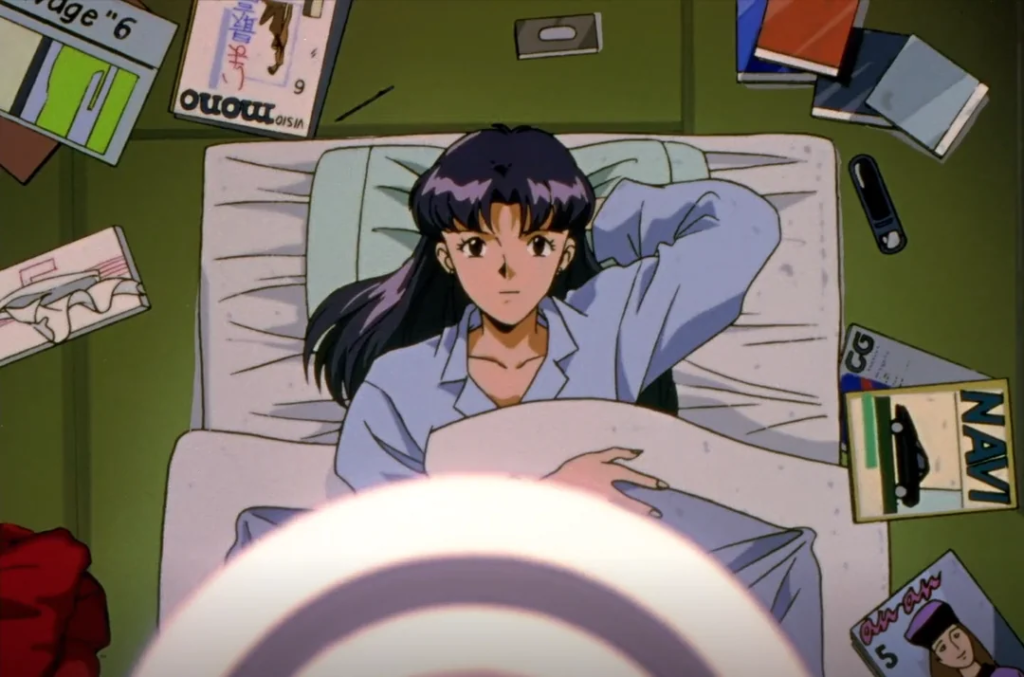

Shinji wants his father’s approval but can’t survive the emotional distance that approval requires. Asuka performs confidence to mask psychological disintegration. Misato pursues intimacy through sexuality while maintaining absolute emotional barricades. Rei embodies disconnection so complete she treats her own death as administrative inconvenience. Every character maintains precise social spacing—close enough to avoid complete isolation, distant enough to prevent actual vulnerability.

The show maps this dilemma geometrically. Watch how characters are framed: Shinji and Gendo in the same room but separated by a desk that might as well be a canyon. Misato and Kaji in bed together, shot from angles that emphasize the space between their bodies. The visual language constantly depicts proximity without connection, bodies sharing frames without sharing emotional space.

The elevator scene in episode twenty-two—ninety seconds of Asuka and Rei standing in silence—does more character work than most series accomplish in full episodes.

It’s just two people failing to speak, filmed in real time. That’s the entire show in miniature.

Anno’s Breakdown Became the Plot

The production history isn’t subtext—it’s primary text. By episode twenty-four, Evangelion’s budget had evaporated and Anno was clinically depressed, a fact he discussed openly in the 1997 documentary “The End of Evangelion Production Report.” The show’s descent into abstraction wasn’t artistic choice alone; it was creative necessity meeting psychological crisis.

Those final episodes, where animation gives way to static sketches and internal monologue, where the plot dissolves into Jungian therapy-speak and the “congratulations” ending rejects narrative closure entirely—they’re not avant-garde for effect. They’re what happens when a creator realizes he’s been projecting his own collapse onto his protagonist and can’t maintain the illusion anymore.

The 1990s Japanese economic collapse provides context. The Lost Decade destroyed the post-war promise that hard work guaranteed stability. Anno came of age in this wreckage, watching the certainties that defined previous generations evaporate. Evangelion captures that specific anxiety: the sense that following the rules, piloting the Eva, doing what you’re told, leads nowhere but deeper dysfunction.

Shinji isn’t just depressed. He’s depressed in the exact register of a generation watching their future disappear while being told their suffering is personal failure.

The Human Instrumentality Project as Suicide Metaphor

Human Instrumentality promises to dissolve individual consciousness into collective unity, ending loneliness by ending selfhood. It’s pitched as evolution. It’s structured as annihilation.

Watch how the concept is introduced: not as triumph but as relief from unbearable consciousness. Characters don’t want transcendence—they want the pain to stop. Instrumentality offers permanent anesthesia disguised as spiritual advancement. The AT Field (Absolute Terror Field) doesn’t just protect the Eva pilots; it represents the barrier of selfhood itself, the boundary that makes you “you” at the cost of being separate from everyone else.

The final act presents a choice between maintaining that boundary—accepting loneliness as the price of individual existence—or dissolving it completely. It’s the depressive’s eternal question: keep feeling this way, or stop feeling at all?

The End of Evangelion makes the metaphor explicit. Third Impact shows humanity merging into primordial unity, individual forms dissolving into orange liquid that looks disturbingly like amniotic fluid. Return to the womb as species-wide regression. Rebirth as death.

Shinji’s choice to reject Instrumentality isn’t heroic triumph. It’s the decision that living with pain might be preferable to not existing at all.

That’s the bleakest hope the series offers, and it barely qualifies as hope.

Misato’s War and Asuka’s Performance

Misato Katsuragi runs from her father’s death straight into a career militarizing children. She drinks alone in her apartment, maintains surfaces—the cheerful act, the professional competence—while the gap between who she pretends to be and who she is widens every episode. Her relationship with Kaji isn’t romance; it’s two people using intimacy as temporary distraction from problems neither can articulate.

The show places her in authority over Shinji while making clear she has no business guiding anyone. It’s not cruel irony. It’s accurate to how institutional dysfunction perpetuates: damaged people managing damaged people, everyone performing competence while barely managing.

Asuka’s arc literalizes the collapse of performance. Her entire identity is constructed as defensive achievement—”I’m the best, therefore I exist, therefore I matter.” When that performance fails during the battle with the Angel Arael, when her mind is invaded and her trauma exposed, she doesn’t just lose a fight. The architecture of her selfhood collapses. What’s left is catatonia, the endpoint when protective mechanisms burn out completely.

The hospital scene in End of Evangelion—Shinji’s violation of Asuka’s unconscious body—is unwatchable by design. It’s the nadir of his self-loathing, the moment when loneliness curdles into violence against the person he can’t reach. The scene exists to make the audience complicit in recognizing how thoroughly these characters have been destroyed by the systems supposed to protect them.

NERV doesn’t save the world. It grinds children into psychological pulp and calls it defense.

The Congratulations Ending and What It Actually Says

Episode twenty-six abandons plot entirely for introspective theater. Shinji sits in a void being interrogated about his existence while the cast congratulates him for achieving… what, exactly? Self-acceptance? The acknowledgment that he might deserve to exist?

The ending infuriated audiences expecting resolution. It’s perfect. The show that spent twenty-five episodes depicting psychological paralysis couldn’t end with conventional triumph because that would validate the very narrative structures it spent deconstructing. Shinji doesn’t defeat the final boss or save the world. He arrives at the bare minimum threshold of not wanting to disappear.

The “congratulations” sequence plays as both genuine and hollow. It’s the participation trophy version of healing—technically positive, substantially empty. But for someone at Shinji’s level of dysfunction, even that minimal self-acceptance represents genuine progress. The show refuses to valorize or mock this. It just presents it: this is what recovery looks like at ground zero.

The End of Evangelion provides the violent counterpart, showing what rejection looks like—Third Impact as the literal apocalypse version of choosing oblivion. Both endings are real. Both happened. The contradiction is the point.

You don’t resolve Evangelion. You choose which collapse resonates more.

What the Show Actually Explains

Neon Genesis Evangelion explains what it’s like when the mechanisms that keep you functional stop working. It explains how institutions exploit damage while calling it purpose. It explains the specific geometry of wanting connection while being structurally incapable of accepting it.

The show doesn’t require theological decoding or frame-by-frame analysis to understand—though those pursuits aren’t wrong. The meaning sits in plain sight: these are people destroying themselves in slow motion, trapped in systems that guarantee their destruction, and the symbols surrounding that destruction don’t make it meaningful.

They just make it look like it means something.

Which might be worse.

Anno created a text that mirrors its own thesis—a narrative that promises coherence, delivers fragmentation, and forces its audience to decide whether the search for meaning matters when the meaning might just be that we’re all too damaged to connect properly. The show’s enduring power comes from its refusal to comfort that anxiety. It anatomizes loneliness without offering easy solutions, depicts psychological collapse without pathologizing it as individual failure, and ends by suggesting that survival—just continuing to exist despite everything—might be the only triumph available.

The angels keep coming. The pilots keep breaking. And somewhere in that cycle, Evangelion explains exactly what it set out to explain: what it feels like to live in your own head when your head is the last place you want to be.