Somewhere between the hundredth kamehameha and the millionth friendship-powered transformation, action anime developed a problem. Fights became calculators. Character A has 9,000 power units, Character B has 12,000, so Character B wins until Character A discovers Ultra Mega Form and the numbers reset. Rinse, repeat, buy the merchandise.

Then some anime remembered that human conflict—the thing battles are supposed to represent—doesn’t actually work like that.

Strategic combat anime operate on a different economy. Victory belongs to whoever reads the room better, plans three moves ahead, or figures out the absurd loophole in their opponent’s apparently unbeatable technique. The protagonist might be weaker, slower, or outgunned. They win anyway because they thought harder about the problem. These shows treat fighting like narrative poker: it’s not about the hand you’re dealt, but how you play it.

The Intelligence Arms Race That Actually Pays Off

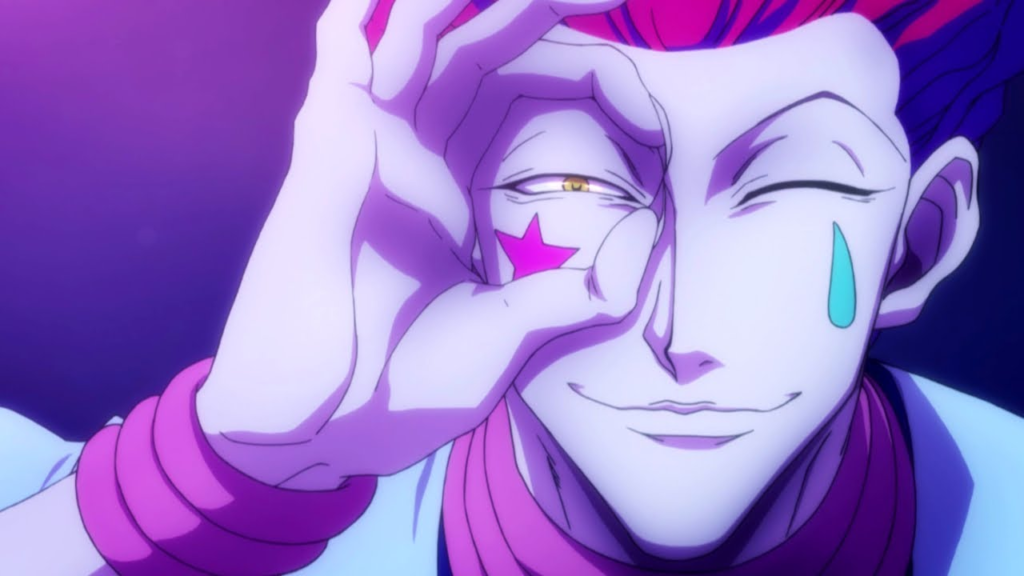

Hunter x Hunter’s Nen system functions as strategic combat distilled into rule structure. Every ability has conditions, costs, and counters. Gon’s jajanken isn’t just “rock paper scissors with aura”—it’s a commitment to telegraphing his attack in exchange for devastating power, which only works if his opponent doesn’t have time to react or misreads his intention.

The Chimera Ant arc pushes this to its logical extreme. Netero versus Meruem isn’t about who hits harder. It’s about whether a human who’s mastered one technique for decades can create enough micro-variations to confuse a being with superhuman processing speed. Netero loses the fight. Wins the war. Different game entirely.

Togashi built this system while dealing with chronic health issues that repeatedly forced Hunter x Hunter into hiatus—a creative constraint that paradoxically produced some of manga’s most intricate combat writing. When you can’t rely on weekly output, every fight needs to justify its existence.

When Nationalism Meets Giant Robots

Code Geass treats mecha battles as military strategy with a supernatural wildcard. Lelouch’s Geass gives him absolute obedience from anyone who makes eye contact—once. The limitation creates the tension. He can’t just Geass his way through every problem because the power has a single-use restriction per person, forcing actual tactical planning around when and how to deploy it.

The Battle of Narita showcases this perfectly. Lelouch doesn’t have the strongest Knightmare Frames. He has geography, misdirection, and one carefully placed Geass command that turns an enemy ace into a involuntary suicide bomber. The episode treats combat like a heist film: setup, execution, the moment where everything almost falls apart, then the reveal that the “mistake” was intentional.

Code Geass aired during a period of increased Japanese anxiety about economic and military relevance in Asia—China’s rise, North Korea’s nuclear program, the memory of economic stagnation. Lelouch’s underdog rebellion against a global superpower resonated as power fantasy specifically because it emphasized strategic cunning over raw force.

Death Note’s Weaponized Paranoia

Light Yagami versus L isn’t action anime in the conventional sense. No one throws a punch for seventeen episodes.

It’s the most action-packed psychological warfare in the medium. Every conversation is combat. Every casual interaction hides three layers of manipulation. The potato chip scene—yes, that scene—works because it transforms eating junk food into a high-stakes operation requiring split-second timing, hidden cameras, and fake television audio. The absurdity is the point. When your battlefield is “convince your opponent you’re not suspicious,” everything becomes a potential tell.

The tennis match episode crystallizes this. Light and L play tennis. They’re also playing “who can extract information while pretending to just play tennis.” The actual tennis doesn’t matter. The game is entirely subtext.

Tsugumi Ohba and Takeshi Obata created Death Note’s cat-and-mouse structure partially in reaction to the battle manga formula they felt had grown stale. The supernatural notebook becomes a MacGuffin—what matters is two hyperintelligent people trying to outthink each other while maintaining social masks. It’s strategic combat stripped to pure psychology.

The Stand Battle Problem-Solving Method

JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure treats fights as puzzle boxes. Stands aren’t measured in power levels—they’re measured in “how weird is this ability and what’s the hidden vulnerability?”

Dio’s The World stops time. Unbeatable, right? Except Jotaro’s Stand development throughout Stardust Crusaders builds toward the reveal that Star Platinum has the same ability, learned through subconscious reaction to time-stop. The final fight becomes a question of “who can move longer in frozen time,” but the real strategy is Joestar family bullshitting: bluffing, improvisation, and using your opponent’s arrogance against them.

Then there’s Yoshikage Kira versus Josuke in Diamond is Unbreakable. Kira’s Killer Queen erases people from existence. His third ability, Bites the Dust, creates a time loop that kills anyone who learns his identity. The solution isn’t overpowering him—it’s tricking Bites the Dust into activating on the wrong person at the wrong time, breaking the loop’s conditions. Araki writes Stand battles like lateral thinking exercises: the answer is never “hit it harder.”

The series deliberately designs Stands with exploitable weaknesses because a fight where the hero just overpowers the villain offers nothing interesting to read or draw. Every ability gets a condition, a range limit, or a logical counter built into its rules.

Why Chess Beats Power Scaling

Strategic combat anime understand something fundamental about tension: uncertainty beats inevitability. When the protagonist wins through superior planning rather than superior genetics, the victory feels earned. The audience gets to participate in the problem-solving instead of passively watching number go up.

Legend of the Galactic Heroes builds entire fleet battles around this principle. Reinhard von Lohengramm and Yang Wen-li don’t win through individual combat prowess—they win through logistics, morale warfare, and reading their opponent’s psychology. A battle might be decided by which admiral correctly predicts whether their opponent will retreat or press an advantage. The ships are window dressing. The real fight is two intellects testing each other’s assumptions.

This reflects the show’s production context: a 110-episode OVA series made for a niche audience of military history enthusiasts and political philosophy nerds, adapted from novels written during the Cold War’s final decade when proxy conflicts were decided by geopolitical maneuvering rather than direct superpower confrontation.

The Problem With Being Smarter Than Everyone

Strategic combat creates a different kind of power fantasy. Instead of “what if I could destroy mountains with my fists,” it offers “what if I could outthink any opponent, no matter how outmatched I am physically?” The appeal is cerebral: pattern recognition, risk assessment, the satisfaction of watching a plan come together.

But it also exposes writing weaknesses faster than power-scaling does. A stupid fight can hide behind spectacle. A strategic battle lives or dies on whether the plan makes sense, whether the opponent’s counter-move feels logical, whether the resolution earns its cleverness. The audience is actively thinking along with the characters, which means they notice the plot holes.

The best strategic combat anime treat this as a feature, not a bug. They let characters make mistakes. Fall for obvious traps. Overthink themselves into worse positions. The humanity in the tactical thinking is what makes it compelling.

Where Brains Meet Breaking Point

These shows offer a corrective to the endless escalation treadmill. There’s no “next level” when your protagonist’s advantage is intelligence. Light doesn’t unlock Super Kira form. Lelouch doesn’t get Geass 2.0 with unlimited uses. The constraints stay fixed. The problems get harder.

That’s the actual tension. Not “will the hero become strong enough,” but “can the hero stay smart enough when everyone else gets smarter too?”

Power levels eventually hit absurdity and collapse under their own weight. Strategic combat just keeps asking: what if the person who thinks fastest wins?