Every anime season, someone declares an adaptation “ruined” before the first episode airs. The manga panels don’t match the trailer. A beloved scene got cut. A character’s hair is the wrong shade of blue. The fanbase mobilizes, armed with side-by-side comparisons and righteous fury, defending source material like it’s sacred text that cannot be interpreted, only obeyed.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: faithfulness is a terrible metric for quality.

The best anime adaptations often succeed precisely because they betray their source material. Not through laziness or disrespect, but through understanding that manga, light novels, and anime are fundamentally different mediums with different storytelling languages. What works on a page can die on screen. What seems essential in text might be narrative dead weight in motion. And sometimes, the original author’s vision needs to be protected from the original author.

This isn’t about defending bad adaptations or excusing studio incompetence. It’s about recognizing that “faithful” and “good” aren’t synonyms—and that the obsession with one often murders the other.

The Faithfulness Fetish

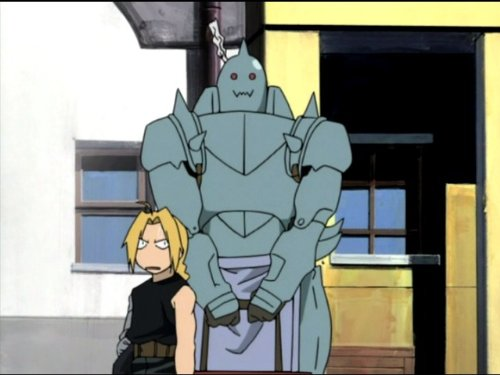

The demand for absolute fidelity to source material is relatively recent in anime history. Older adaptations routinely diverged, condensed, or completely reimagined their sources without the internet’s collective meltdown. Fullmetal Alchemist (2003) overtook its manga, invented an entire second half, and is still considered one of the medium’s best works. The audacity wasn’t the problem. The execution was the point.

Modern anime production has calcified around a different model. Adaptations function primarily as advertisements for their source material, engineered by production committees where the manga publisher often holds veto power. This isn’t artistic collaboration—it’s brand protection. The anime exists to drive volume sales, which creates perverse incentives to preserve every panel regardless of how it translates to animation.

The result is a generation of viewers who mistake loyalty for craft. Who believe the best compliment an adaptation can receive is “it’s exactly like the manga.” As if the director, storyboarders, voice actors, and composers are just expensive photocopiers, faithfully reproducing someone else’s work without adding interpretation, emphasis, or vision.

That’s not adaptation. That’s embalming.

Medium is the Message

Manga and anime operate on fundamentally different temporal and spatial rules. Manga readers control pacing—they can linger on a panel, flip back to earlier pages, or race through action sequences at whatever speed suits them. Anime viewers are passengers on a fixed timeline, experiencing moments in real-time dictation by the director and editor.

This difference annihilates the premise of panel-for-panel adaptation. A manga page might contain six panels spanning three seconds of action, with careful control of eye movement and information revelation. Translating that “faithfully” to anime means either padding those three seconds into glacial stillness or condensing six carefully calibrated beats into incomprehensible blur.

K-On! director Naoko Yamada understood this instinctively. The source manga was a four-panel gag strip with minimal plot and even less character depth. A faithful adaptation would have been twelve episodes of flat jokes and cute girls doing cute things—watchable but forgettable. Instead, Yamada invented an entire visual language: feet shots to ground emotion, lens flares to capture ephemeral teenage joy, and extended sequences of silence that the manga never contained because manga doesn’t have silence—it has white space, which isn’t the same thing at all.

The anime transcended its source because Yamada recognized that adapting isn’t about preserving panels. It’s about translating intention across mediums, which sometimes means abandoning the text entirely.

When Betrayal Works

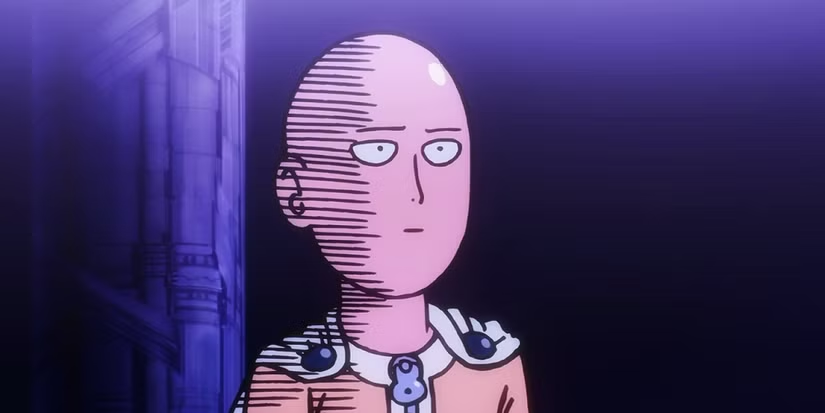

Mob Psycho 100 anime director Yuzuru Tachikawa faced a unique challenge: adapting ONE’s deliberately crude art style into polished animation without losing its essential character. The “faithful” approach would preserve the wonky proportions and rough linework. Instead, Tachikawa betrayed the literal visuals to capture their spiritual essence—surreal, expressive action sequences that feel like ONE’s manga even while looking nothing like it.

The show’s visual identity came from interpreting what the art was trying to communicate rather than what it literally depicted. Season one’s finale took a relatively straightforward manga fight and transformed it into a psychedelic explosion of symbolic imagery, abstract color, and emotional devastation that wasn’t in the original panels but was absolutely in the story’s DNA.

This is adaptation as translation, not transcription. Finding the anime equivalent of a manga’s techniques rather than mechanically copying them.

Contrast this with Tokyo Ghoul‘s later seasons, which desperately tried cramming massive manga arcs into twelve-episode seasons. The adaptation was technically “faithful” in that it hit most major plot points, but the compression strangled pacing, gutted character development, and turned complex moral arcs into incomprehensible plot summaries. It followed the source material off a cliff, prioritizing fidelity over functionality.

Faithfulness without craft is just expensive stenography.

The Trap of Completeness

The production committee system creates a paradox: adaptations need to hook viewers into buying the source material, but committee members often mandate including everything because cutting feels like admitting something wasn’t important. This is how you get anime that adapts thirty manga chapters into twelve episodes, speedrunning through crucial character beats to ensure every plot point gets checked off the list.

The Promised Neverland season two stands as a masterclass in how not to handle this pressure. Faced with adapting complex, multi-arc manga content, the production chose to invent an anime-original ending that condensed, simplified, and fundamentally misunderstood what made the source compelling. They betrayed the manga badly—but not through creative reinterpretation. Through panic and incompetence.

This is the critical distinction. Good betrayal comes from understanding the source so deeply that you know what can be sacrificed and what’s load-bearing. Bad betrayal comes from not understanding it at all, or from commercial pressures that prioritize speed over substance.

The Director’s Gamble

Giving directors creative freedom carries risk. For every Naoko Yamada transforming K-On!, there’s a dozen adaptations where directorial vision clashed disastrously with source material. The question isn’t whether directors should have autonomy—it’s whether they’ve earned it through demonstrated understanding of what makes the source material work.

Monster director Masayuki Kojima took the opposite approach from Yamada: near-total faithfulness to Naoki Urasawa’s manga, adapting all eighteen volumes across seventy-four episodes with minimal deviation. This worked because Urasawa’s manga was already paced for anime adaptation, and because Kojima recognized that his role was creating cinematic atmosphere rather than restructuring narrative. The “betrayals” were subtle—camera angles, soundtrack choices, voice acting interpretations—but they transformed a great manga into exceptional anime without changing a single plot point.

The lesson isn’t that faithfulness is always wrong. It’s that the decision to be faithful or deviate should come from creative necessity, not fear or dogma.

Some stories need reimagining. Some need reverent translation. The skill is knowing which approach your source material demands.

The Author Question

Western discourse often treats manga authors as absolute authorities whose vision must be preserved at all costs. But authorial intent is messier than this suggests. Manga serialization is brutal—weekly or monthly deadlines, editor interference, publisher demands, and the constant threat of cancellation shaping creative decisions as much as artistic vision.

Sometimes the anime has luxuries the manga never did: time to plan endings, freedom from editorial mandates, or simply the benefit of hindsight to fix narrative problems the author couldn’t address during serialization. The original creator isn’t always right about their own work, especially when that work was created under commercial pressures that no longer apply.

This isn’t disrespect. It’s recognition that creation is messy, collaborative, and constrained by material reality. The manga isn’t a perfect crystallization of pure vision. It’s what got made under specific conditions at a specific time. The anime is made under different conditions and can make different choices—sometimes better ones.

What Actually Matters

Strip away the discourse about faithfulness, and what makes an anime adaptation genuinely good becomes clearer: internal consistency, emotional resonance, technical craft, and narrative coherence. Whether these come from strict adherence to source material or radical reinvention is purely contextual.

The best adaptations understand their source material well enough to know when to follow it and when to forge new paths. They recognize that manga and anime are different art forms with different strengths, and that honoring the spirit of a work sometimes means abandoning its letter.

Faithfulness is a tool, not a virtue. Use it when it serves the story. Abandon it when it doesn’t.

The real betrayal isn’t changing the source material. It’s adapting without understanding why the source material worked in the first place. That’s the sin no amount of panel-perfect accuracy can absolve.

The next time someone declares an adaptation ruined because it diverged from the manga, ask them: what matters more, matching the panels or matching the feeling? Because those aren’t always the same thing.

And sometimes, the greatest act of loyalty is knowing when to break the rules.