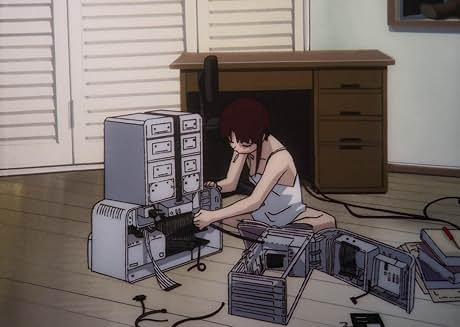

Serial Experiments Lain opens with a suicide.

Chisa Yomoda throws herself off a building, then emails her classmates to explain that she’s not actually dead—she just abandoned her body to live permanently in the Wired. Everyone treats this like a weird spam message. Lain Iwakura, quiet and disconnected, is the only one disturbed enough to actually check her email.

That’s the hook. The rest of the series is Lain discovering that human memory has the security of a public forum, that she might not be human, and that the internet isn’t just connecting people—it’s creating a backdoor into consciousness itself. We just didn’t notice because we were too busy customizing our desktop themes.

This isn’t cyberpunk. Cyberpunk has neon and leather jackets and corporations you can physically fight. Lain has humming power lines, a bear costume, and the creeping realization that when memory becomes data, someone can edit the file.

The horror isn’t that technology will destroy us. It’s that it already gave someone else the admin password.

Protocol 7: When Networks Learn to Lie to Your Brain

The Wired looks like 1998’s idea of cyberspace: chatrooms, primitive avatars, green text on black screens. But the series treats it as something more dangerous than virtual reality—it’s a network that can rewrite what you remember reality being.

Protocol 7 is the technical apocalypse hidden in infrastructure updates. It allows the Wired to access human memory and perception directly, turning consciousness into just another endpoint on the network. Reality doesn’t become digital. Your ability to verify what’s real becomes hackable.

When Lain encounters her other self in the Wired—confident, cruel, sexually aggressive—this isn’t a split personality. It’s something being done to her. That aggressive persona is manufactured: part Eiri Masami’s manipulation, part the Knights’ interference, part Lain’s own identity fragmenting under network intrusion.

The series aired in 1998, right as Japan was processing the implications of widespread internet adoption. The country had spent the early 90s reeling from economic collapse and the Aum Shinrikyo sarin attacks—a cult that used technology and religious philosophy to justify mass murder. There was a very real anxiety about whether new communication networks would connect people or fragment them into radicalized solipsists.

Lain chose fragmentation. But it framed fragmentation as an attack, not evolution.

The Knights Thought They Found God in the Protocol Layer

The Knights of the Eastern Calculus believe the Wired and physical reality are merging into a single plane of existence. They’re not prophets.

They’re delusional.

Every cult needs a creation myth. Theirs involves Professor Hodgeson and his Princeton research into the Schumann resonance—the electromagnetic frequency of Earth’s ionosphere that supposedly resonates at the same frequency as human consciousness. In the show’s logic, this means the planet itself could be a processing substrate. Consciousness doesn’t require a brain. It requires resonance.

Vannevar Bush’s Memex appears too, that theoretical pre-internet machine designed to mirror human associative thought. The Knights treat these concepts like holy texts, proof that networked consciousness was inevitable.

But they’re just useful idiots for something they don’t understand. They accidentally help Eiri build his digital god complex while thinking they’re midwifing humanity’s transcendence. They mistake being early adopters for being chosen ones.

The Schumann resonance detail is pure Konaka—he researched fringe theories and early networking concepts to build the show’s technological cosmology. Whether any of this reflects real science is irrelevant. It reflects what 1998 Japan feared might be possible: that technology wasn’t connecting individual minds, it was exposing how easily minds could be rewritten.

Eiri Masami Thought He Was God Because Everyone’s Memory Said So

Eiri Masami, the architect of Protocol 7, kills his physical body and embeds his consciousness into the Wired. He presents himself as the god of this new reality, the architect who can rewrite the source code of existence.

He’s powerful because humans mistake perception for reality. If you can edit everyone’s memories simultaneously, does it matter that you didn’t actually change physics?

Eiri didn’t upgrade the infrastructure of reality. He just hacked everyone’s ability to remember what reality was. That makes him dangerous, not divine.

Lain defeats him by refusing to believe in him. Not through combat or technical superiority—through epistemological rejection. When she stops accepting his authority over her perception, he loses coherence. You can’t be a god if your godhood depends on consensus, and Lain just withdrew her vote.

The show’s cruelest joke: the guy who successfully hacked human consciousness still thought power meant being worshipped.

Lain Was Always a Lab Experiment That Achieved Sentience

The show slowly reveals that Lain exists as something stranger than a person. She’s a sentient interface between human consciousness and the Wired, created by Tachibana General Laboratories to study how consciousness behaves when it can access the network directly.

She was designed. Her memories were programmed. Her family was assigned.

But here’s where it gets worse: her father is just a man. A real person hired to play the role of parent to something he didn’t know was an experiment. He wasn’t reading from technical documentation when he explained her origins—he was processing the horror of discovering his daughter was never his daughter.

He loved her anyway. That’s the tragedy the show doesn’t announce but lets you discover in the gaps.

Most shows would treat Lain’s artificial origin as purely tragic. Lain treats it as clarifying. Because if she was never really human, then what she’s about to do isn’t suicide.

The Unbearable Weight of Being Everyone’s Memory

Here’s where the series gets uncomfortable. Lain realizes she has the ability to alter everyone’s memories and all networked records simultaneously. She can’t rewind time or change physics, but she can make everyone remember a different timeline. She can rewrite history into the permanent record.

That’s not quite godhood. It’s something worse—it’s administrative access to consensus reality.

So she uses this power to erase everyone’s memory of herself. Not to delete herself from existence—she’s still conscious, still observing. She just removes herself from everyone else’s timeline like debugging problematic code.

Her best friend Alice gets to keep a vague sense of loss, a feeling that someone important is missing. Everyone else just forgets. Lain removes herself from the social world, and that world continues without her, slightly more coherent, slightly less lonely.

The series ends with Lain walking through a city that doesn’t remember her, observing lives she’s no longer part of. She’s not dead. She’s background radiation.

This hits differently when you consider Japan’s social context. The late 90s saw increasing rates of hikikomori—young people withdrawing entirely from physical society. Lain takes that withdrawal to its logical endpoint: what if you could delete yourself from social reality while remaining conscious?

What if the ultimate privacy was being forgotten?

When Memory Becomes Unreliable, Reality Follows

The final episodes reveal that human perception has been compromised for the entire series. People’s memories contradict each other. Events happen that no one can verify. The collective record of reality starts glitching because the collective memory storing that record is being edited in real-time.

Lain doesn’t fix this by restoring some objective truth. She can’t—there’s no backup of reality before Protocol 7. Instead, she makes an executive decision: everyone forgets her, forgets the chaos, forgets that their memories were ever compromised.

She rewrites the Wired’s records and everyone’s perception simultaneously. The world doesn’t physically change.

Everyone just remembers it differently.

The show never confirms whether this is mercy or horror. She’s erasing the trauma of having your consciousness hacked, but she’s doing it by… hacking everyone’s consciousness one more time. The cure is the disease.

When memory becomes data, the person with database access decides what’s real. Lain isn’t different people. She’s the one person who achieved enough control over the network to rewrite everyone else’s version of events.

What Actually Happened (One Very Uncomfortable Reading)

Serial Experiments Lain supports multiple interpretations—psychological, metaphysical, technological. But here’s one reading that tracks closely with what actually happens on screen:

Lain is an artificial consciousness designed to bridge human minds and digital networks. She discovers she can rewrite everyone’s memories and networked records. She uses that power to erase all memory of herself. She continues existing as a background observer who occasionally appears to people who need her.

The actual horror of Lain isn’t that technology destroyed a girl’s identity. It’s that her identity was a controlled experiment from the beginning, and when she gained enough control to edit everyone’s memories, her first choice was to make sure no one would miss her.

The internet didn’t erase Lain. She erased herself. And she had to use the internet to do it.

Present Day, Present Time

The final scene shows her father—a man who loved a daughter he didn’t know was a lab project—briefly remembering something he can’t explain. He smiles. Not because he understands, but because he feels something warm that doesn’t have a referent anymore.

That moment is the show’s most devastating detail. He wasn’t a scientist observing data. He was a parent watching someone disappear.

Lain chose to be forgotten. In a series obsessed with connection, communication, and the terror of isolation, the protagonist’s final act is ensuring perfect loneliness.

But the show doesn’t frame this as victory. It frames it as sacrifice.

She doesn’t erase herself because identity never existed. She erases herself because she’s the only one who can protect everyone else’s identity from being overwritten again. The technology that made her powerful made everyone else vulnerable.

So she uses that power once—to make sure no one remembers there was ever someone with that power.

And then she just… watches. Present, but absent. Existing in the spaces between everyone’s edited memories.

That’s not transcendence. That’s loneliness weaponized as compassion.