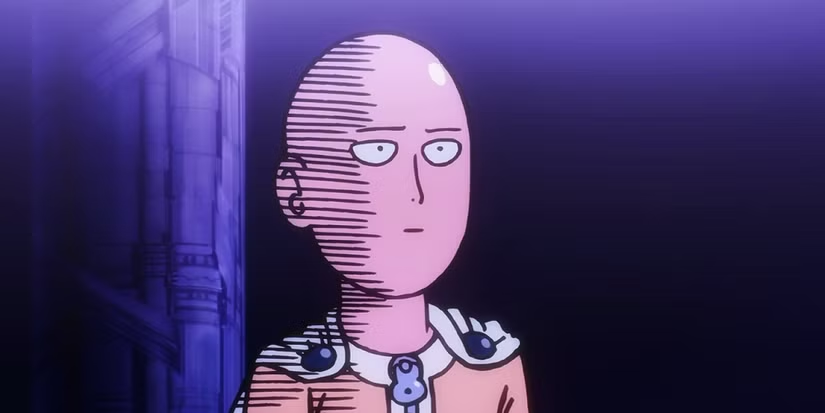

Most anime about overpowered protagonists understand the assignment: give viewers the visceral thrill of watching someone annihilate their problems with overwhelming force. It’s escapism with a clear transaction—your protagonist suffers indignities for exactly long enough to make the payoff satisfying, then releases enough psychic energy to restructure continental plates while the soundtrack goes hard.

Mob Psycho 100 sets up this exact contract in its opening minutes, then spends three seasons methodically redefining it. What makes this fascinating isn’t just that the show transforms the expected catharsis—it’s that the transformation itself becomes the point. Every moment where Mob could solve his problems by flattening someone into the pavement, he doesn’t. And the show frames this restraint not as noble self-sacrifice, but as the only ethical position in a world where power and worth have become catastrophically confused.

The Bait-and-Switch Written Into the DNA

The opening episode of Mob Psycho 100 deploys every genre signal for “protagonist will eventually go nuclear and it will be glorious.” Shigeo Kageyama possesses psychic abilities potent enough to accidentally atomize buildings. He works under a charlatan mentor. He’s bullied at school. He harbors feelings for a girl who barely registers his existence. This is the recipe—simmer for three episodes, add catalyst, watch explosion.

Except when the percentage counter hits 100% early in the series, Mob doesn’t obliterate the delinquents who’ve been tormenting him. He loses control, but the aftermath is framed as failure, not triumph. The show treats these early explosions not as setups for better, more justified eruptions later, but as evidence that raw power solves nothing: power is not the solution, it’s the thing that needs solving.

This becomes the pattern ONE (the creator) hammers into bedrock throughout the series. The Telepathy Club arc, the Mogami possession, the confrontation with Claw, even Ritsu’s early attempts to develop his own abilities—every narrative beat constructs the perfect justification for Mob to cut loose, and every time he finds a way around it. It’s like watching someone refuse to use a fire extinguisher during an inferno because they’re concerned about water damage. Except the show gradually reveals that most fires don’t actually require extinguishers; they require questioning why everything’s so flammable in the first place.

The Mogami Arc: Turning the Victim Fantasy Inside-Out

The Mogami Keiji arc might be the most deliberately uncomfortable iteration of this transformation. Mogami, a spirit whose power rivals Mob’s, traps him in a fabricated reality where everyone—classmates, teachers, parents—treats him with open contempt. The psychological imprisonment feels endless, designed specifically to break Mob’s ideology of restraint. The arc’s thesis from Mogami’s perspective: “Once you’ve suffered enough, violence becomes justified. Become the predator or stay prey forever.”

This is the fantasy most power-escalation anime secretly sell. The protagonist endures just enough abuse to make their eventual rampage feel righteous. Mogami’s psychological torture chamber isn’t unusual—it’s just making the subtext text, doing what a dozen other shows do but with the cruelty dialed to explicit. The fabricated world is less a trap and more a contract offer: accept that strength exists to dominate, and you can stop hurting.

Mob’s response breaks the genre. He doesn’t overcome Mogami by unlocking a deeper power level or discovering that friendship gives him strength. He survives by simply refusing the premise. When Mogami manufactures a scenario where Mob’s “parents” beg him to use his powers to hurt his tormentors, Mob still won’t. Not because he’s transcendently good, but because he’s recognized that the cost of solving problems through domination is becoming the kind of person whose problems require domination to solve. It’s a recursive nightmare, and Mob opts out.

The arc concludes not with Mob destroying Mogami through superior force, but with Dimple—his companion spirit who’d been operating on pure self-preservation logic—choosing to intervene while Mob refuses to abandon his convictions. The resolution comes from both Mob’s ethical commitment and Dimple’s unexpected solidarity, not supremacy. Mogami’s entire philosophy gets defeated by people refusing to engage with its terms. Which, as philosophical rejections go, hits harder than any psychic blast the animation budget could render.

Reigen’s Accidental Deconstruction of Strength

Reigen Arataka operates on a principle that should get him killed within three episodes: he’s a fraud with zero psychic ability who routinely confronts espers capable of deconstructing matter at the molecular level, and his primary defense mechanism is saying things confidently while dressed business-casual. He’s a walking satire of every mentor archetype, except the show gradually reveals he’s also the only adult in the entire series who understands what strength actually means.

The Claw arc’s seventh division showdown demonstrates this perfectly. When Ishiguro and his esper squad prepare to execute Reigen for being a normal human in a psychic supremacist organization, Mob transfers his power temporarily. What follows is visually spectacular—Reigen dismantling the division with borrowed abilities—but the actual victory doesn’t come from the power itself. It comes from Reigen’s absolute conviction that psychic ability is just a skill, like Excel proficiency or parallel parking, and people who build their entire identity around it are compensating for having nothing else.

His speech to the Scars—”Having psychic powers doesn’t make you any better than anyone else”—reads like it should be the protagonist’s hard-won realization in the finale. Instead, it’s delivered mid-series by a sweaty conman who’s been winging it since the opening credits. The show positions Reigen’s philosophy as obviously correct and treats the entire psychic hierarchy as a shared delusion that only persists because everyone agreed to take it seriously. The borrowed power lets Reigen survive long enough to deliver the philosophy; the philosophy is what actually matters.

This becomes even sharper in the press conference arc, where Reigen faces public humiliation not for being a fraud, but for claiming abilities he doesn’t have. The show lets him fall completely—no last-minute save, no vindication through power. His redemption comes from Mob valuing him despite the fraudulence, which lands because the series has spent dozens of episodes demonstrating that the only thing Reigen ever offered worth having was his perspective on what matters. The actual exorcisms were always beside the point.

Reigen operates like a man speedrunning interpersonal crises while preventing everyone else’s apocalyptic mental breaks through weaponized improvisation. His survival strategy shouldn’t work in a world where power equals value, but the show’s entire architecture is built to prove that world wrong.

The Bodybuilding Club as Philosophical Argument

When Mob joins the Body Improvement Club, the show could have played it as ironic contrast—psychic god learns to do pushups, ha ha. Instead, it becomes the clearest articulation of the series’ ethics. The club members have zero supernatural ability and are deeply aware that Mob could vaporize them by sneezing too hard, but they treat him with straightforward respect because he shows up and tries. The metric isn’t capacity, it’s effort toward self-improvement.

This arrangement inverts the standard shonen training arc. Usually, the protagonist joins a club or dojo to unlock latent abilities or discover the power of teamwork. Mob joins the bodybuilding club specifically to develop something his psychic powers can’t provide: the physical discipline required to confess to Tsubomi. His powers are irrelevant to the goal. They might even be counterproductive, since the entire pursuit is about proving he can accomplish something through sustained, unglamorous work.

The club members become Mob’s most reliable support system not through narrative contrivance, but because they’re the only people in his life who consistently value what he does over what he can do. When everything collapses in the final arc and Mob’s running through the city in a dissociative state, the Body Improvement Club shows up not because they can fight ???%, but because their friend is suffering and that’s sufficient reason to act. It’s perhaps the only moment in modern anime where a group of teenagers with zero combat capability inserting themselves into a psychic apocalypse reads as sensible rather than suicidal.

Their presence reframes the entire climax. The question isn’t “Can Mob control his power?” but “Can he recognize that the people who value him don’t need him to be powerful?” The club members standing in front of ???% while completely outmatched isn’t heroic sacrifice—it’s proof that the relationship was never transactional. They’re not there because Mob might save them later. They’re there because that’s what you do.

The Tsubomi Problem: When the Fantasy Collapses Entirely

The entire series orbits around Mob’s desire to confess to Tsubomi Takane, and the show’s final act systematically dismantles any possibility of that confession mattering in the way viewers expect. Tsubomi isn’t a prize to be won through character development or a catalyst for Mob unlocking his true potential. She’s a regular person with her own life, about to move away, who’s been largely unaware that Mob’s been building his entire identity around someday being worthy of her attention.

The finale orchestrates the cruelest possible timing: Mob finally works up the courage to confess just as his psychic powers spiral into an extinction-level event. ???% (the autonomous manifestation of Mob’s suppressed emotions) tears through the city while Mob—conscious but disconnected—tries desperately to reach Tsubomi before she leaves. It’s every romantic subplot’s worst-case scenario: the confession happens during an apocalypse, delivered by someone barely holding consciousness together, to a person who has every reason to be terrified.

And Tsubomi’s response is… kind. Not reciprocal, not transformative, just kind. She doesn’t confess hidden feelings or validate Mob’s years of pining. She thanks him for telling her and acknowledges his effort. The show grants Mob exactly zero romantic catharsis while simultaneously having him save the city from his own fractured psyche. The final sequence plays both achievements—confession and preventing annihilation—as equivalently important, which functionally means the confession matters more. Mob cares more about telling Tsubomi how he feels than about having leveled several city blocks.

This is the show’s most complete redefinition of the power fantasy structure. In a traditional arc, Mob would save the city, and that heroism would either win Tsubomi’s affection or provide closure that he’s outgrown her. Instead, Mob saves the city almost incidentally while pursuing something entirely mundane, and the mundane thing doesn’t pan out, and that’s fine. The resolution isn’t that he gets what he wanted—it’s that he survives wanting it, and that survival required accepting help from everyone who valued him despite his uncertainty about whether he deserved it.

The finale essentially argues that the real fantasy isn’t unlimited power—it’s the idea that power could ever address the things people actually want. Mob’s psychic abilities can restructure matter but can’t make him confident. They can level cities but can’t make Tsubomi reciprocate. The show spends 25 episodes demonstrating this gap and then refuses to bridge it, because bridging it would validate the premise that strength and worth are connected.

Japan’s Economic Ruins and the Anxiety of Potential

ONE created Mob Psycho 100’s original webcomic in 2012, two decades into Japan’s “Lost Decades”—the extended economic stagnation following the 1991 asset bubble collapse. An entire generation grew up watching their parents’ promise of lifetime employment and predictable advancement evaporate into irregular work, wage stagnation, and the anxiety that effort might not correlate with outcome. The cultural mythology of hard work leading to success hadn’t disappeared; it had become hollowed out, a structure still standing but no longer load-bearing.

Whether or not ONE intended this as explicit commentary, Mob Psycho 100 reads like it’s in direct conversation with this context. The show’s supernatural abilities function as a literalization of potential—raw capacity disconnected from actual value. Every esper in the series faces the same fundamental question: what do you do when you have power that society claims should matter, but which doesn’t actually address any of your real problems? Mob has abilities that should guarantee him status, respect, and easy solutions, but he’s still lonely, anxious, and uncertain about his worth. His power is simultaneously immense and useless for the things he cares about.

This maps onto the experience of Japan’s post-bubble generation, who were promised that their education and effort would translate into security, only to discover that the economy couldn’t honor those promises. The metaphor functions whether conscious or not: having the “right” attributes (elite education, psychic powers) stops guaranteeing outcomes (stable employment, self-worth) when the system that previously validated that exchange collapses.

The show’s treatment of Claw—the terrorist organization of psychic supremacists—becomes especially pointed in this reading. Claw’s ideology is that natural ability should determine hierarchy, that the powerful deserve to rule the powerless. This is just meritocracy stripped of its polite justifications, and the show positions it as straightforwardly authoritarian. Not because hierarchy is inherently evil, but because any system that derives human worth from capacity creates a nightmare for everyone who doesn’t fit the capacity being measured. The series suggests that contemporary society has been operating on Claw’s logic while pretending it’s something else.

Reigen’s entire character becomes legible as a response to this anxiety. He has no special abilities but refuses to accept that this makes him worthless. His fraudulence isn’t the problem—it’s his honesty about the fraudulence that threatens the system. Everyone else in the psychic world maintains the fiction that their abilities make them fundamentally superior; Reigen just points out that this superiority hasn’t actually made them better people or solved their problems, and the entire power structure treats this observation as more dangerous than any esper attack.

The show’s refusal to let Mob solve problems through power mirrors the economic reality that individual exceptional ability can’t fix structural dysfunction. Mob can’t psychically blast his way into Tsubomi’s affection or into self-confidence for the same reason exceptional workers can’t productivity-boost their way out of systemic wage stagnation. The problem isn’t individual capacity—it’s that the system claiming to reward capacity is broken.

The Running Sequence: Choosing the Harder Answer

The climax of the series—Mob running through the destroyed city while friends, family, and former enemies physically support him toward Tsubomi—operates as the show’s clearest statement on strength. ???% is tearing apart the landscape, an autonomous manifestation of every emotion Mob’s suppressed through his commitment to restraint. It’s pure psychic power divorced from conscious control, and it’s annihilating everything.

The resolution doesn’t come from Mob overpowering ???%. It comes from Mob accepting it. The reintegration happens when Mob stops viewing his emotions (including the destructive ones, the petty ones, the ones that want to hurt people) as problems to be suppressed and starts treating them as parts of himself that deserve acknowledgment. ???% isn’t defeated; it’s recognized. The destruction stops not because Mob became stronger than his own power, but because he stopped fighting the fact that he contains the capacity for destruction.

This should feel like a cop-out—”the real power was accepting yourself all along”—except the show’s already spent three seasons demonstrating that self-acceptance is the hardest, least glamorous work available. Mob’s been pursuing it through the bodybuilding club, through tutoring Ritsu, through continuing to show up for Reigen despite the fraudulence. The final reintegration isn’t a revelation; it’s the conclusion of a process that’s been happening in the margins of every psychic battle.

And the people carrying Mob through this moment are precisely the ones who never needed him to be powerful: the Body Improvement Club, Tome, Mezato, even Teru (who started the series as a psychic supremacist and gradually became someone who valued Mob for reasons having nothing to do with power). Their presence argues that the relationships that matter are the ones built on something other than transactional capacity.

The sequence refuses to make Mob’s psychic abilities the solution. They’re not irrelevant—the kid still needs to stop leveling the city—but they’re also not what saves him. What saves him is the network of people who kept choosing to value him when he was uncertain whether he had value. It’s collective, unglamorous, and completely resistant to power-scaling metrics. You can’t measure it in percentages.

Why the Redefinition Matters

Mob Psycho 100 could have delivered a perfectly functional power fantasy. The animation budget was there. ONE’s storyboarding could absolutely sell the catharsis of Mob cutting loose. The audience would have eaten it up. Instead, the show constructs that fantasy meticulously and then reframes it at every opportunity, not out of contempt for the genre but out of something closer to concern.

The series suggests that the power fantasy genre has been selling a specific lie: that the solution to vulnerability is capacity, that feeling weak stops hurting once you become strong enough. Mob has unlimited capacity and still feels weak. The disconnect doesn’t get resolved through more power—it gets resolved through recognizing that vulnerability isn’t actually solvable, and that’s not a failure. The people who matter to Mob aren’t the ones he can protect; they’re the ones who chose to stand with him when protection was impossible.

This redefinition of catharsis through connection rather than domination isn’t soft or gentle. It’s the show’s most rigorous ethical position, maintained across three seasons despite constant narrative pressure to abandon it. The restraint itself becomes the thesis: that recognizing you could destroy something and choosing not to is harder, more valuable, and more indicative of actual strength than any explosion could ever be. Even when the explosion would be completely justified. Even when everyone’s begging for it. Especially then.

The show ends with Mob slightly more confident, still uncertain, and moving forward without the guaranteed validation he spent the series pursuing. No romantic resolution, no psychic supremacy, just the ongoing work of showing up as yourself even when yourself feels insufficient. Which, as philosophical victories go, photographs terribly but apparently lasts.