Here’s something nobody wants to admit about Your Lie in April: the show is terrified of quiet. Not the pregnant, meaningful kind of quiet where characters sit with their feelings like adults attempting therapy. The actual quiet. The kind where Kousei might have to look Kaori in the eye for more than twelve seconds without a Chopin étude buying him time to figure out what the hell he’s supposed to say.

Instead, we get performances. Endless, gorgeous, meticulously animated performances that consume substantial portions of episodes while actual plot development gets shoved into the commercial break like emotional baggage into an overhead compartment. Episode 22 dedicates a massive chunk of its runtime to Kousei’s final performance of Chopin’s Ballade No. 1 in G minor—an extended, uninterrupted sequence that prioritizes spectacle over conversation. That’s not storytelling. That’s a recital with narrative footnotes.

And look, the music is stunning. Studio A-1 Pictures threw remarkable resources at making these sequences feel like visual poetry, with abstract watercolors and symbolic imagery that would make a film school graduate weep. But somewhere between the fourth and fifth extended performance sequence, you start to notice the pattern: every time the show needs to process something difficult—grief, mortality, romantic confession, the fact that Kousei’s mother weaponized Beethoven into child abuse—it just… plays another song.

The Language Everyone Refuses to Speak

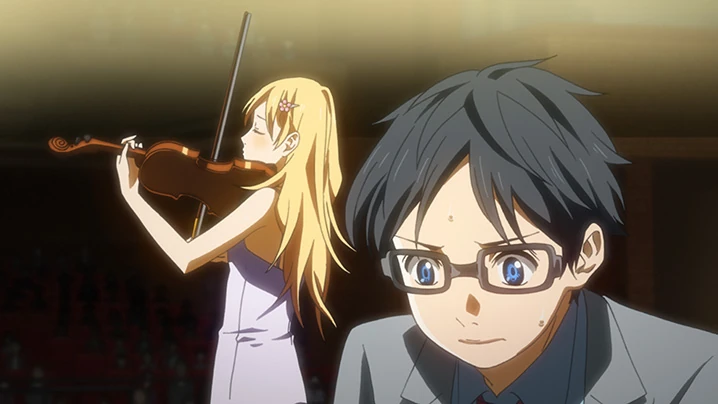

Watch how the show structures its emotional climaxes. Episode 4 builds toward Kousei’s breakthrough performance of Mozart’s “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” variations—the moment he’s supposed to reconnect with music after his trauma. The episode frames this as character development, but look at what it’s actually avoiding: the conversation about why Kaori collapsed during her performance, why she keeps lying about her health, why everyone in this show communicates through Chopin instead of actual sentences.

The performance becomes a narrative placeholder where difficult conversations should be. It’s the equivalent of responding to “we need to talk about your mother’s death” with “hold that thought, I’m going to play Rachmaninoff for the next several minutes.” Which, to be fair, is exactly what Kousei does. Repeatedly.

The show treats these sequences like they’re character development, but they’re closer to emotional intermissions. Beautiful, meticulously crafted delays before anyone has to finish an uncomfortable sentence.

The Gala Concert as Grief Quarantine

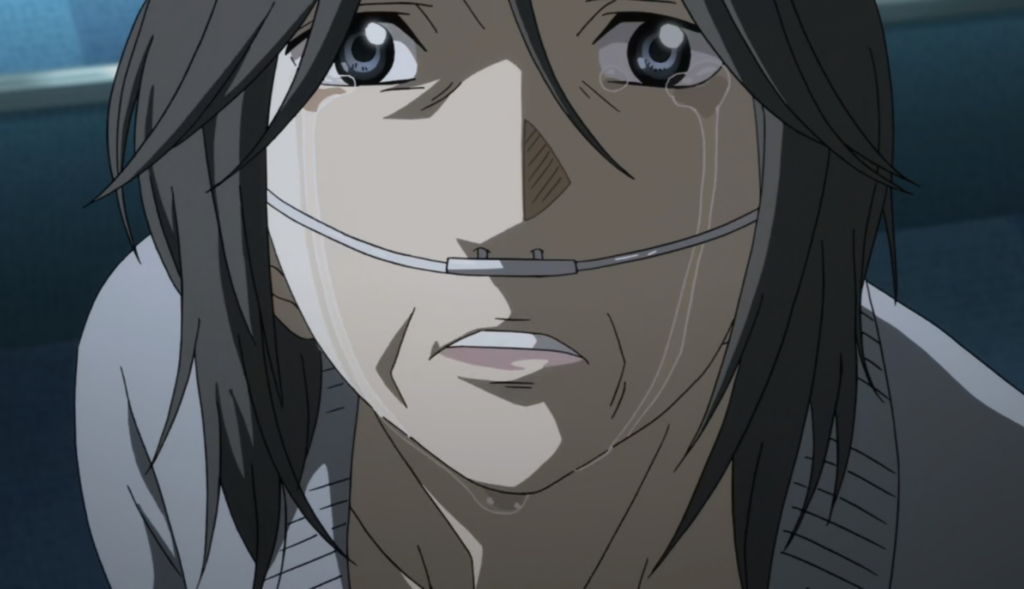

Episode 22, “Spring Wind,” commits perhaps the show’s most elaborate act of emotional displacement. Kaori is dying—not metaphorically, not dramatically, but literally down the hall in a hospital room while Kousei plays in the gala concert. The episode structures this as poetic parallel: she plays violin in his mind, he plays piano on stage, and together they perform a duet across the boundary between life and death.

Except that’s not what’s happening. What’s actually happening is that Kousei is on stage performing Chopin while the girl he loves is alone, dying, in a hospital room he never visited enough. The show frames the performance as connection, but it’s fundamentally about distance. He’s not with her. He’s doing the one thing he’s always done when feelings become unbearable: disappearing into music like it’s a bomb shelter.

The performance dominates the episode—rendered with all the visual splendor A-1 Pictures could manufacture: cherry blossoms, abstract color fields, a phantom Kaori playing alongside him in a sequence that looks like someone spilled a watercolor set into the animation cells. It’s breathtaking. It’s also a profoundly lonely way to say goodbye.

The show never quite acknowledges this. Instead, it treats the performance as transcendent resolution—Kousei has “overcome” his trauma, “reached” Kaori, “accepted” his mother’s death, all through the power of playing really good piano. But those scare quotes are doing Olympic-level heavy lifting. He hasn’t processed anything. He’s just gotten better at performing through it, which is absolutely not the same thing as healing. It’s the emotional equivalent of learning to smile at a funeral—a survival skill masquerading as recovery.

When Silence Costs More Than Spectacle

Here’s where things get interesting from a production standpoint. Animation is expensive, and different types of scenes carry different costs and risks. Dialogue scenes—especially emotionally complex ones—require nuanced facial expressions, subtle body language, careful timing. They’re director-intensive, animator-intensive, and terrifyingly easy to get wrong.

Musical performance sequences follow more predictable patterns. You can plan them, storyboard them, assign them to specialized animation teams. Studio A-1 Pictures assembled skilled animators who could make fingers on piano keys feel like emotional crescendos. Sakuga (high-quality animation) is expensive, but it’s scalable expensive. Emotional intimacy is artisan expensive. Each scene has to be handcrafted.

This creates an interesting incentive structure—though I want to be clear this is speculation about industry pressures, not documented fact about this specific production. In early 2010s anime, there was enormous market pressure to deliver “event” moments—scenes that would trend on social media, get turned into clips, sell Blu-rays. An extended performance of Beethoven with sakuga-quality animation and visual metaphors? That’s promotional gold. Two characters sitting in a hospital room having an honest conversation about death? That’s Tuesday.

Whether or not budget drove creative choices here, the effect is the same: the show consistently chooses spectacle over conversation, performance over presence.

The Love Letter Nobody Reads

Episode 11 is where the show’s avoidance tactics become almost comical in their transparency. Kaori finally, finally tries to tell Kousei the truth—about her feelings, about her illness, about the lie in the title—and the show immediately drowns her out with Kreisler’s “Liebesleid” (literally “Love’s Sorrow,” because subtlety died in a traffic accident). She plays while internally monologuing about everything she can’t say out loud, and then the episode just… moves on.

This happens constantly. Characters use performance as confession-by-proxy, assuming the audience will decode their emotional subtext through musical selection. Tsubaki processes her jealousy by watching Kousei perform in episode 8. Kaori communicates her entire emotional arc through her violin performances—in episode 4’s Kreutzer Sonata, episode 11’s Kreisler, episode 16’s Saint-Saëns—because actually speaking words is apparently for people who don’t have terminal illnesses and perfect pitch.

The show treats this as romantic and profound—characters understanding each other through music in ways words never could. But that’s just poetry for “nobody in this show can have a direct conversation.” When Kaori’s letter finally arrives in episode 22, after she’s dead and can no longer be contradicted or questioned, it’s the show’s ultimate admission: the only safe emotional honesty is posthumous.

The Mother-Shaped Hole in the Chopin

Let’s talk about what these performances are actually avoiding: Saki Arima, Kousei’s mother, who beat perfectionism into her son with the same hands that were dying of illness. The show handles this trauma with all the directness of a politician’s apology—technically acknowledged, never quite confronted.

Kousei’s trauma isn’t subtle. His mother’s abuse is framed through synaesthetic horror—he sees her ghost, hears her voice, loses his ability to hear the piano keys when he plays. It’s PTSD rendered as magical realism, and it’s genuinely disturbing. But the show’s resolution isn’t therapy or genuine processing. It’s more performing. Kousei “overcomes” his trauma by playing through it, literally, in competition after competition, until eventually his brain decides the ghost isn’t scary anymore.

The show presents this as healing, but it’s closer to dissociation with better production values. Every time we might have to sit with Kousei’s actual grief—about his mother’s death, about her abuse, about the impossible tangle of loving someone who hurt you—there’s another competition, another performance, another extended musical sequence to distract us with beauty.

Episode 7’s performance of Chopin’s Étude Op. 10, No. 4 is the template. Kousei sees his mother’s ghost, has a panic attack on stage, and then plays through it while the animation shows us abstract representations of his emotional state—dark water, drowning, sudden light. It’s visually stunning and emotionally… vague. We see the metaphor of his struggle, but we never actually see him process it. He just performs until the ghost goes away, which is less “healing” and more “learning to dissociate productively.”

Episodes 9 and 10 split Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata across their runtime—Kousei and Kaori performing together in what’s framed as breakthrough, connection, the moment they truly understand each other. But understanding through performance isn’t the same as understanding through conversation. It’s safer. More beautiful. And completely non-reciprocal, because you can’t argue with someone’s interpretation of Beethoven.

The Audience That Never Speaks

The strangest part of Your Lie in April‘s performance obsession is how it treats audiences. Every competition, every gala, every informal concert happens in front of crowds who barely exist. They’re sketched in as impressionistic shadows, reacting in unison like a Greek chorus written by someone who’s never met a second person. Their function isn’t to be human—it’s to be a mirror for the performer’s internal state.

When Kousei plays “well,” the audience loves it. When he plays “badly” (which is to say, emotionally), they’re confused or disappointed. But we never see individual reactions, never hear specific responses. The audience is a monolith because the performances aren’t actually for them—they’re for us, the anime viewers, who are watching a character perform emotions they can’t speak.

This is what makes the final performance in episode 22 so fundamentally lonely. Kousei is playing for an audience of hundreds, but the only person he wants to reach—Kaori—is either dead or dying in a hospital room. The show deliberately leaves the timeline ambiguous, never specifying exactly when she dies relative to his performance, because that ambiguity feels more romantic than precision. He’s performing connection while being profoundly, irretrievably alone.

The show frames this as beautiful. And it is—visually, musically, it’s stunning. But beauty and emotional honesty aren’t the same thing. Sometimes beauty is just what we use to make loneliness look intentional.

What the Manga Knew

Naoshi Arakawa’s original manga handles performances differently—not because it’s more emotionally direct, but because manga can’t play music. The performances exist as panels with musical notation and extended internal monologue. They still dominate emotionally, but they can’t dominate time the way the anime’s sequences do.

The anime expands these moments significantly, which makes sense from a production standpoint—it’s showcasing what animation can uniquely accomplish. But the expansion changes the story’s pacing and its relationship with emotional processing. The manga uses music as punctuation in an emotional sentence. The anime uses it as the subject-changing you do when someone asks an uncomfortable question.

This isn’t necessarily a flaw—the anime is doing something distinct from its source material, creating a different kind of experience. But it is a choice, and that choice consistently favors spectacle over vulnerability, performance over conversation.

When the Music Finally Stops

Your Lie in April ends not with a conversation, but with a letter—Kaori’s final words, read in voiceover while Kousei sits alone in a park. It’s posthumous emotional honesty, which is the safest kind because the dead can’t ask you to reciprocate. The letter says everything she never said while alive: that she loved him, that she lied about loving Watari, that she learned to play violin specifically to perform with him. It’s a confession without consequence.

And then the credits roll over—what else?—a piano performance. Because of course they do.

The show’s final message, intentional or not, is that performance is safer than presence. That beauty can substitute for honesty. That if you play something beautifully enough, you don’t have to actually say what it means. Kousei ends the series as a better pianist but roughly the same level of functional emotional communicator—he’s just learned to channel everything through Chopin instead of dealing with it directly.

Which is fine, probably. Lots of people live their entire lives that way—turning feelings into productivity, vulnerability into performance, grief into art. It works until it doesn’t. But Your Lie in April never interrogates this. It just plays another song and hopes we’re too moved by the music to notice that nobody’s actually talking.

The show’s greatest achievement and its deepest flaw are the same thing: it’s so beautiful that you almost don’t notice everyone’s drowning. The performances are breathtaking. The animation is gorgeous. The music is transcendent. And underneath all of it is a boy who never learned to say “I’m hurting” without playing Chopin first, a girl who died before anyone made her explain herself, and a mother who abused her son in the name of love and never faced a single consequence beyond becoming a convenient ghost for visual metaphors.

The music never stops because if it did, someone might have to finish a sentence. And that—actual, direct, unadorned emotional honesty—turns out to be the one thing Your Lie in April can’t quite perform.